Prepared statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources’s hearing to review the implementation of the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

Main Points

- Outdoor recreation on public lands has never been more popular, and the LWCF faces challenges and opportunities amid a changing recreation landscape.

- Public land managers should have flexibility to use LWCF funds for their greatest conservation needs, including land management and maintenance.

- Conservation and recreation funding models that incorporate outdoor recreation users are more stable, reliable, and significant than models reliant on politics.

- LWCF land acquisitions and easements should strategically aim to open access to existing public lands.

Introduction

Chairman Murkowski, Ranking Member Manchin, members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you to provide testimony on the Land and Water Conservation Fund. My name is Brian Yablonski, and I am the executive director of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), a conservation research institute based in Bozeman, Montana.[1] PERC has a nearly 40-year history dedicated to exploring market-based solutions to conservation challenges. Prior to moving to Montana, I was the chairman of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, where I served as a commissioner for 14 years.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund has funded projects in virtually every county in the nation. Since its creation to facilitate outdoor recreation more than half a century ago, it has provided the means to build trails, construct local parks, open access to federal lands, and support myriad other recreation-related projects. In short, the program has done excellent work.

With permanent reauthorization of the program and calls for full funding of it, Congress is wise to review the implementation of it, particularly because of changing recreation and conservation challenges on public lands. I will aim to highlight some of the realities facing the future of recreation on public lands and ways that the LWCF could help address them.

Outdoor recreation on public lands has never been more popular.

Outdoor recreation is on the rise.[2] The Bureau of Economic Analysis has found that outdoor recreation accounts for $412 billion of gross domestic product—or more than 2 percent of the entire U.S. economy. The bureau also estimates that the sector has consistently grown faster than the national economy in recent years.[3] The Outdoor Industry Association, a trade group that represents retailers, outfitters, and similar recreation businesses, estimates that the sector generates $887 billion in consumer spending and 7.6 million jobs.[4] Roughly half of Americans ages 6 and up participate in outdoor recreation activities. Whether running or kayaking, fishing or climbing, bird-watching or camping, or doing any other activity outdoors, Americans go on approximately 11 billion recreation outings each year.[5]

Public lands provide the backdrop for much of that recreation. The Outdoor Industry Association calls public lands and waterways “the backbone of our outdoor recreation economy.”[6] From national forests and wildlife refuges to national parks and wild and scenic rivers, some of the most prized landscapes and destinations in the country are found on public lands. And the popularity shows in visitation trends. Recreation visits to national parks have surged 16 percent in the past five years. That’s nearly 50 million additional visitors, and closer to 60 million if you count the peak visitation years of 2016 and 2017. And 28 individual park sites set visitation records last year.[7] Similarly, visitation to national forests has steadily increased over the past decade.[8] The same story applies to many other federal recreation lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Reclamation, as it does for numerous state parks from coast to coast.[9]

The LWCF faces challenges and opportunities amid a changing recreation landscape.

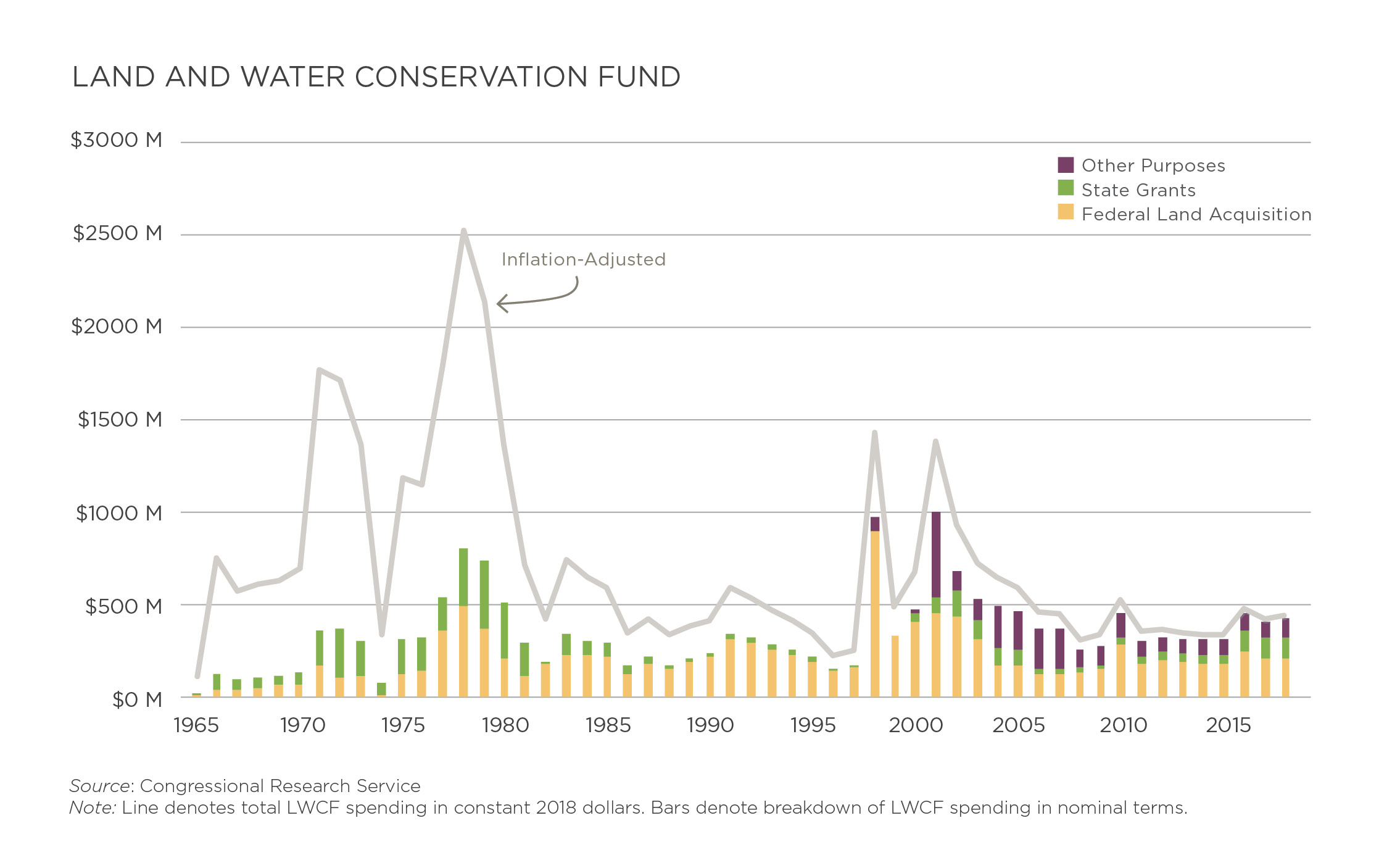

The LWCF has been a significant source of conservation and recreation funding since it came into effect in 1965. Congress created the program to facilitate participation in recreation and strengthen the “health and vitality” of U.S. citizens.[10] The fund is authorized at up to $900 million per year, subject to the annual appropriations process. Historically, it has been used for three purposes: land acquisition by federal land management agencies for outdoor recreation, grants made to states for outdoor recreation purposes, and “other purposes,” which include special requests for funding made by presidents since 1998.[11]

The growth of the outdoor recreation sector presents new challenges for the LWCF in the 21st century. Over recent years, recreation appropriations to federal land management agencies have been stagnant or declining after adjusting for inflation.[12] Coupled with increased visitation, that means that public land managers are having to serve more people with fewer resources. The consequences show up in the stressed infrastructure on public lands, such as deteriorating hiking trails, campgrounds, wastewater systems, employee housing, and roads—the very things that allow people to recreate on our majestic lands. The backlog for trail maintenance alone across national parks and forests is $740 million.[13] And after spending a day last month in Yellowstone National Park with Superintendent Cam Sholly to see firsthand the deferred maintenance challenges, it is clear employee housing is in poor condition and in need of critical work. Conservation is not only about taking care of what you own but also taking care of those we charge with conserving our natural treasures.

After years of postponing many repairs for lack of funding, agencies within the Interior Department are grappling with $14.2 billion in deferred maintenance projects.[14] The Forest Service faces its own backlog of $5.2 billion in overdue maintenance.[15] In other words, today there is a total deferred maintenance backlog of more than $19 billion on public lands.

The permanent reauthorization legislation passed in early 2019 stipulated that no less than 40 percent of LWCF appropriations shall be spent on federal land acquisition and no less than 40 percent on stateside grants.[16] That means the vast majority of LWCF funding cannot be devoted to other purposes that can enhance outdoor recreation on our federal lands, such as helping address the $19 billion deferred maintenance backlog.

Furthermore, the LWCF is funded primarily by revenues from the oil and gas leases on the Outer Continental Shelf. It has become increasingly clear that there is competition over and pressure on these revenues. For one thing, the level of annual spending for LWCF approved by Congress each year under the fund has fluctuated greatly over time and in recent years has consistently been only about half of the maximum allowed by law. What’s more, federal energy revenues are not only the primary source for LWCF, but also potentially for the proposed Restore Our Parks Act and the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, among other conservation initiatives, resulting in trade-offs between land and water conservation, wildlife conservation, and the care and maintenance of our public lands, not to mention other national priorities.[17]

And finally, at the same time there is a move to fully fund LWCF at $900 million annually, there are also environmental organizations and policymakers advocating for the reduction or elimination of offshore energy production, which would dry up the very source used to fund the program.[18]

These issues all present challenges for the LWCF as we try to keep pace with the growing recreation sector and the conservation and management needs of public recreation lands. Fortunately, there are policy options that could address several of these challenges and improve the effectiveness of the LWCF program in the future.

Public land managers should have flexibility to use LWCF funds for their greatest conservation needs, including land management and maintenance.

As our recreation priorities and needs on public lands evolve, public land managers need appropriate tools to address both current and future management challenges. The LWCF toolbox may have been appropriate when the program was created; however, it appears fairly limited today.

Funding decisions entail trade-offs. Appropriations made through the LWCF for either federal or stateside purposes obviously means that those resources cannot be put to other uses, regardless of the conservation priorities that might be facing public land managers. Beginning in 1998, appropriations under the program began to be used for various “other purposes,” including maintenance, ecosystem restoration, and other aims.[19] The LWCF would benefit from more flexibility within the broader federal purposes component to address such needs, whether deferred or cyclic maintenance, land management, or other conservation and recreation purposes.[20] This is especially true as the allocation split of the program was locked in with permanent reauthorization.

Most glaringly, given the massive maintenance needs on existing federal lands, it would be sensible to allow funding flexibility to address deferred maintenance to improve recreation opportunities. For instance, a recent former director of the National Park Service acknowledged that the deferred maintenance backlog was a higher priority than acquiring inholdings within parks.[21] Yet in other contexts, cyclic maintenance—the routine upkeep that can ward off more costly future repairs—might be more important than deferred repairs.

Relatedly, while the LWCF has funded a small amount of forest management in recent years, it would benefit from more flexibility to address such needs.[22] In some places and contexts, land acquisition will be less imperative than conservation priorities that can improve the condition of existing forests and rangelands through wildfire prevention, weed control, or mitigation of drought impacts. Currently, up to 82 million acres of forests are in need of restoration, more than one-third of the entire National Forest System.[23]

The national park superintendents, forest supervisors, and other managers who steward our public lands day to day are the ones best positioned to know what those on-the-ground priorities are. The LWCF would be more effective if the program had more flexibility to respond to these sorts of bottom-up signals about conservation needs.

If anything about the future of the program can be taken for granted, it’s that funding priorities will shift over time. In 1965, a minimum threshold of 40 percent of funding for federal acquisition may have made perfect sense. Whether that remains the case in 2019 is probably less clear. What’s almost certain is that at some point in the next 50 years, the same rigid threshold may no longer be appropriate. Yet the reauthorization language entrenches that reality, which serves to weaken the program.[24]

Every acre that the federal government acquires comes bundled with obligations to manage and maintain that land in perpetuity. Unless Congress passes the Restore Our Parks Act or some similar fund—which, as noted above, is competing in part for the same revenue source—there is no LWCF-like fund for maintenance and management. The billions of dollars in deferred maintenance on existing public lands and our other land management needs attest to that truth, and it’s one that we should keep in mind when making decisions about future land management. Outdoor recreation should be at least as much about quality as it is quantity.

Conservation and recreation funding models that incorporate outdoor recreation users are more stable, reliable, and significant than models reliant on politics.

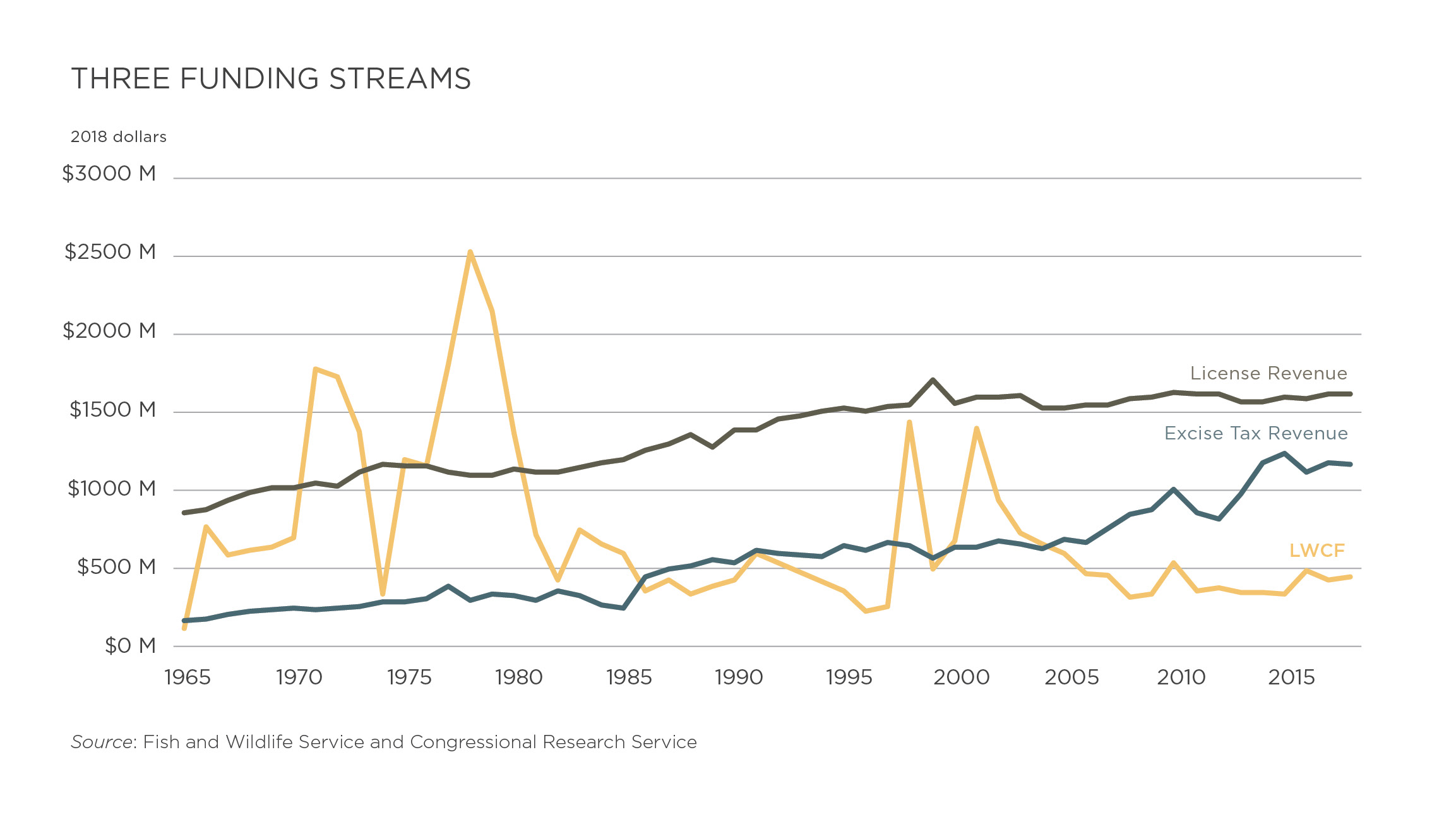

The historical funding record of the LWCF tracks more like an EKG readout than a reliable and predictable trendline. While the program’s funding record has been irregular, unpredictable, and subject to much political wrangling, conservation and recreation funds that rely on users have proven to be much more reliable.

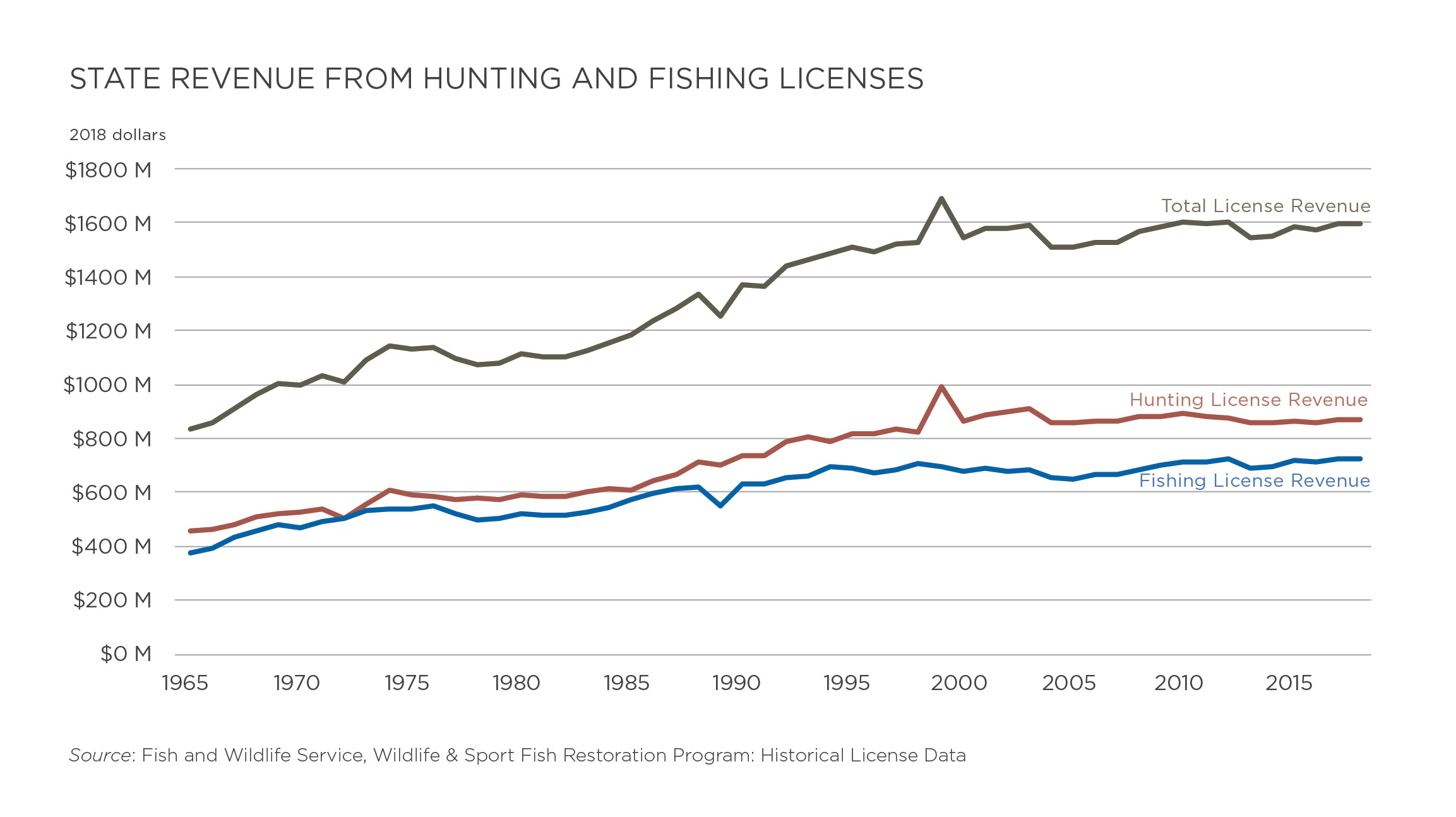

Take, for example, the North American Wildlife Model: The collective budgets of America’s state fish and wildlife agencies total more than $5 billion, and roughly 60 percent of their funding comes from sources related to users—hunters and anglers.[25] The largest portion is revenue from state hunting and fishing licenses. In 2018, license sales generated about $1.6 billion for states.[26] In addition to being a significant chunk of money, these revenues have also been extremely stable for half a century. Because they are generated by users, dedicated to specific purposes, and necessary to draw down as a match for federal excise tax dollars, they are largely insulated from the political whims of legislatures.

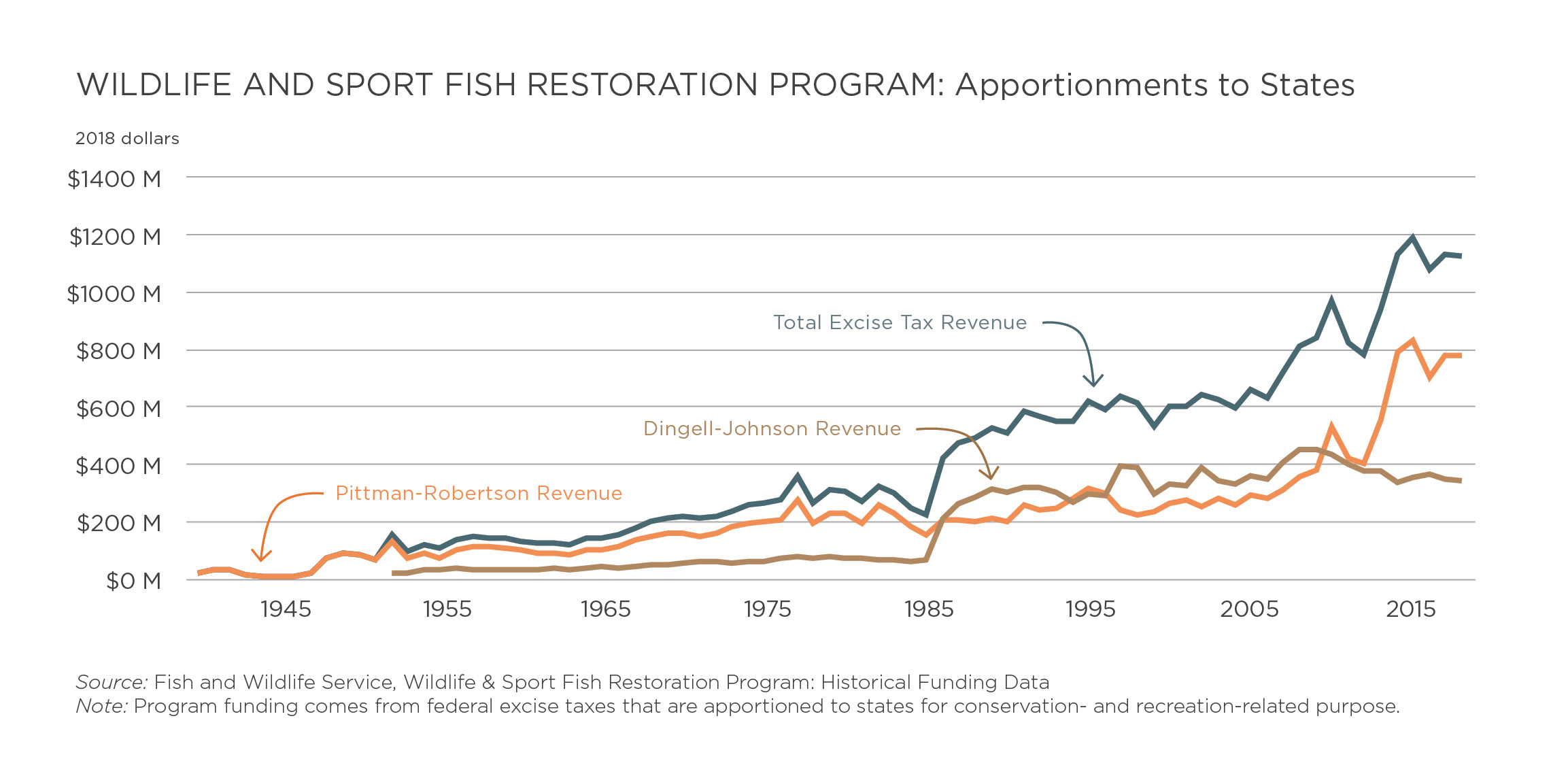

The second-largest source of funding for state fish and wildlife agencies is revenue from federal excise taxes on firearms, ammunition, bows and arrows, fishing tackle, rods and reels, boat fuel, and related items. These funds are distributed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the Wildlife Restoration Program and the Sport Fish Restoration Program, created by the Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson Acts, respectively. In 2018, the two programs combined provided more than $1.1 billion to state fish and wildlife agencies.[27] The excise tax revenues collected by the federal government are distributed to the states and generally require a state-to-federal funding match of one to three.[28] The match component means that states and hunters and anglers are putting skin into the game and have more reason to make sure those federal dollars are put to good use.

Likewise, many hunters and anglers know that they pay into the conservation system, and they are proud of it. In fact, these users lobbied for implementing the excise taxes in the wake of the Great Depression, as fish and wildlife agency budgets were dwindling.[29] As a former state fish and wildlife commissioner, I can tell you that pride means these funding sources have an extra level of accountability absent from general appropriations.

The user-pays models also provide relatively tight feedback loops—or at least much tighter than appropriations dollars. Funding tied to demand for recreation means that if recreation demand grows, revenue grows too. This creates a virtuous cycle whereby funding is generated to steward environmental amenities, restore habitat, and conserve wildlife. With these models, as the recreation sector grows, so does the funding for managing public recreation assets.

Comparing the long-term trends of these two funding streams and the LWCF is illustrative. After adjusting for inflation, state revenues from hunting and fishing licenses have proven to be remarkably stable over time. The roughly $1.6 billion in revenue that they yielded in 2018 was also nearly four times larger than the $425 million appropriated from the LWCF last year. In the same vein, state funding derived from the federal excise taxes on sporting goods have proven to be consistent and substantial. These sources provided more than $1.1 billion to states in 2018.

Similarly, recreation fees collected at national parks, national forests, and other federal recreation lands have several benefits when compared to general appropriations. Under the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act, certain sites can charge and collect fees on federal lands and waters, either for entrance to a site or for use of an amenity such as a developed campground.[30] Sites that collect fees can retain and spend 80 percent of their receipts without further appropriation. This framework aligns incentives by giving managers reason to cater to visitors and enhance the experience on public lands. While not perfect, flexibility from locally retained fee revenues allows superintendents who have the most knowledge about park needs to make decisions about where to spend revenues. It also frees managers of parks, forests, and other sites from wrangling over appropriations for resources that can be funded by fee collections.

Over the past decade, total revenues collected by federal agencies under FLREA have increased by 42 percent in real terms, and virtually all of that increase has occurred over the past five years in lockstep with increasing visitation. In 2018, such receipts totaled $404 million—almost as much as the $425 million appropriated through the LWCF.[31] As Denali National Park Superintendent and three-decade employee of the park service Don Striker has put it: “The bottom line is that fees are now an integral part of our funding. Long ago, Congress realized it could not meet parks’ needs through annual appropriations, and legislators thus authorized us to keep our revenues. The National Park Service should embrace using fees to pay for visitor services.”[32]

The original aim of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act was to provide recreation opportunities to all Americans.[33] Tying some portion of its funding to the original beneficiaries of the act, including hikers, kayakers, whitewater rafters, climbers, mountain bikers, campers, wildlife watchers, skiers, and their gear purchases, would be in line with that aim. It would convert “stoke” into real conservation funding.[34] It would also tap a growing market that is placing increased demands on our public lands.

Furthermore, if user-generated funds, either through user fees and/or a nominal gear excise tax, were incorporated into the federal portion of the program as some sort of match for appropriations dollars, then recreationists could take pride in knowing they are acting as public lands stewards by providing dedicated funding to conservation and recreation. They might even enhance their standing in the federal appropriations process, having real skin in the game and bringing resources to bear.

The stateside LWCF program already incorporates a match component, as do the Fish and Wildlife Service programs that direct federal excise tax dollars to state wildlife conservation. And in fact, sportsmen and -women pay into the conservation system twice—by buying licenses and paying excise taxes—so a funding mechanism that allows other types of recreationists to more directly pay into system is hardly far fetched.

The fact that user-pays-user-benefits funding sources are tied to recreationists helps ensure that the funds promote responsible stewardship of the public lands that serve as some of our greatest recreation assets. The incentive structure created by such funding mechanisms has clear advantages. The funds are reliable and significant sources of recreation funding, two things that are less true of the modern LWCF. The programs also have clear constituencies, which has likely helped bolster the accounts from being raided for other purposes.

The LWCF would benefit enormously from an approach that ties its funding directly to users rather than perpetually being at the mercy of appropriations.

LWCF land acquisitions and easements should strategically aim to open access to existing public lands.

When Congress permanently reauthorized the LWCF in 2019, the legislation specified that for future spending approved under the program, at least 40 percent must be allocated for federal purposes, and at least 40 percent must go to the stateside program.[35] Given those realities, some of the most sensible and efficient acquisitions will be strategic ones that can open access for hunters, anglers, and recreationists to “locked up” public lands.

Landlocked public lands are lands that cannot be accessed by public roads or adjoining public lands, requiring landowner permission, easements, or purchases of land from landowners. These landlocked public lands are often a result of the historic checkerboard ownership patterns of the West. In some states, even public land sections that touch at parcel corners cannot be accessed without permission from all adjoining landowners.[36]

A 2018 report published by the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and onX found that 9.5 million acres of public lands in the West are landlocked—accessible only with permission from private landowners.[37] In my home state of Montana, the number is 1.52 million acres. To the extent additional land acquisition is needed, it makes sense that those acquisitions should focus on such areas, whether clearing “bottlenecks” to existing lands, smoothing out checkerboarded lands, or otherwise. It also makes sense to use the LWCF to attempt to negotiate easements, voluntarily negotiated with landowners, which could cost significantly less in tax dollars and keep land in the local tax base. These land acquisitions or easement purchases would generally involve smaller, more surgical and strategic purchases that would open up to sportsmen and recreationists tens of thousands of acres already owned by the public.

Conclusion

Now is the time to review the implementation of the LWCF in light of permanent reauthorization of the program. By promoting flexibility, involving user-pays models, and strategic acquisitions where necessary, we can make sure the LWCF can meet the challenges and opportunities presented by a growing recreation sector and the demands of the 21st century and beyond.

The LWCF has a storied record of affording Americans recreation opportunities. Responsible conservation means prioritizing the greatest conservation needs. Through these responsible improvements to the LWCF, we can ensure our public lands are conserved and enjoyed well into the future.

[1] PERC—the Property and Environment Research Center—is a nonprofit research institute located in Bozeman, Montana, dedicated to improving environmental quality through markets and property rights. PERC’s staff and associated scholars conduct original research that applies market principles to resolving environmental problems.

[2] A recent report published by PERC documents trends in outdoor recreation on public lands. Parts of this testimony are adapted from the report. “How We Pay to Play: Funding Outdoor Recreation on Public Lands in the 21st Century,” by Tate Watkins. PERC Public Lands Report. May 2019.

[3] “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account: Updated Statistics for 2012-2016.” Bureau of Economic Analysis. September 20, 2018, and “Outdoor Recreation Satellite Account, Prototype Estimates, 2012-2016.” Bureau of Economic Analysis. February 14, 2018.

[4] ”The Outdoor Recreation Economy.” Outdoor Industry Association. 2017.

[5] “Outdoor Participation Report 2018.” Outdoor Industry Association. July 17, 2018.

[6] Supra note 4, p. 3.

[7] National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics, and “National Park Service visitation tops 318 million in 2018.” National Park Service. March 5, 2019.

[8] “National Visitor Use Monitoring Survey Results: National Summary Report 2016.” U.S. Forest Service.

[9] Supra note 2 for more background on increases in recreation visits to public lands.

[10] Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965, P.L. 88-578, 78 Stat. 897. 54 U.S.C. §§200301 et seq. The text of the law had been codified at 16 U.S.C. §§460l-4 et seq. It was recodified under P.L. 113-287 to 54 U.S.C. §§200301 et seq.

[11] “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues,” by Carol Hardy Vincent. Congressional Research Service Report RL33531. August 17, 2018.

[12] Supra note 2 for background on trends in recreation appropriations.

[13] “Forest Service Deferred Maintenance.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. Audit Report 08601-0004-31. May 2017; “Servicewide NPS Asset Inventory Summary.” National Park Service. September 30, 2018.

[14] “Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009-FY2018 Estimates and Issues,” by Carol Hardy Vincent. Congressional Research Service Report R43997. April 30, 2019.

[15] Supra note 13.

[16] John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act. P.L. 116-9. § 3001. March 12, 2019.

[17] For background on competition over federal energy revenues, see “Legislative Proposals for a National Park Service: Deferred Maintenance Fund,” by Laura B. Comay. Congressional Research Service Report IF10987. February 19, 2019.

[18] For example, see “Drilling, LWCF bills pass after marathon markup,” by Kellie Lunney. E&E News. June 20, 2019.

[19] “Land and Water Conservation Fund: Appropriations for ‘Other Purposes,’” by Carol Hardy Vincent. Congressional Research Service Report R44121. May 14, 2019.

[20] See “A New Landscape: 8 Ideas for the Interior Department.” PERC Public Lands Report. March 9, 2017.

[21] “Examining the Spending Priorities and Missions of the National Park Service in the President’s FY 2016 Budget Proposal.” House Natural Resources Committee, Subcommittee on Federal Lands Oversight Hearing. March 17, 2015. During testimony by National Park Service Director Johnathan B. Jarvis, Rep. Tom McClintock asked: “What’s the higher priority: the deferred maintenance backlog or new land acquisitions?” Jarvis answered: “Well, if I had to make that kind of ‘Sophie’s choice,’ I’d say it’s the maintenance backlog.”

[22] Supra note 19 for general background on the Forest Legacy Program, which aims to acquire or preserve through easements forests that might otherwise be converted to other uses.

[23] “Restoring Forest Health: We Need to Pick Up the Pace,” speech by Mary Wagner. U.S. Forest Service. January 31, 2014.

[24] The same is true of the 40 percent threshold for the stateside program; however, acquisitions under the stateside portion of the program do not add to federal maintenance needs.

[25] “The State Conservation Machine.” Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and the Arizona Game and Fish Department. 2017.

[26] Historical License Data. Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[27] “Secretary Zinke Announces More Than $1.1 Billion for Sportsmen & Conservation.” U.S. Department of the Interior. March 20, 2018.

[28] “Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program.” Program Brochure. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. October 2014.

[29] “Leave No Trace?,” by Tate Watkins. PERC Reports Vol. 36 No. 2. December 6, 2017.

[30] Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act. 16 U.S.C. §6802.

[31] Supra note 2.

[32] “Washington’s backward funding: How national parks are encouraged to defer maintenance,” by Don Striker. The Hill. February 20, 2019.

[33] Supra note 11.

[34] “Your stoke won’t save us,” by Ethan Linck. High Country News. May 14, 2018.

[35] Supra note 17.

[36] “Finding a Way In,” by Paul Queneau. Montana Outdoors. October 2014.

[37] “Off Limits, But Within Reach: Unlocking the West’s Inaccessible Public Lands.” Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership and onX. August 26, 2018.