Earlier this year, the black-capped vireo, a formerly endangered songbird from Texas and Oklahoma, was declared recovered and removed from the Endangered Species Act list. The announcement was the capstone of a decades-long collaboration between the federal government, states, conservation groups, and property owners to address threats to the species and restore habitat.

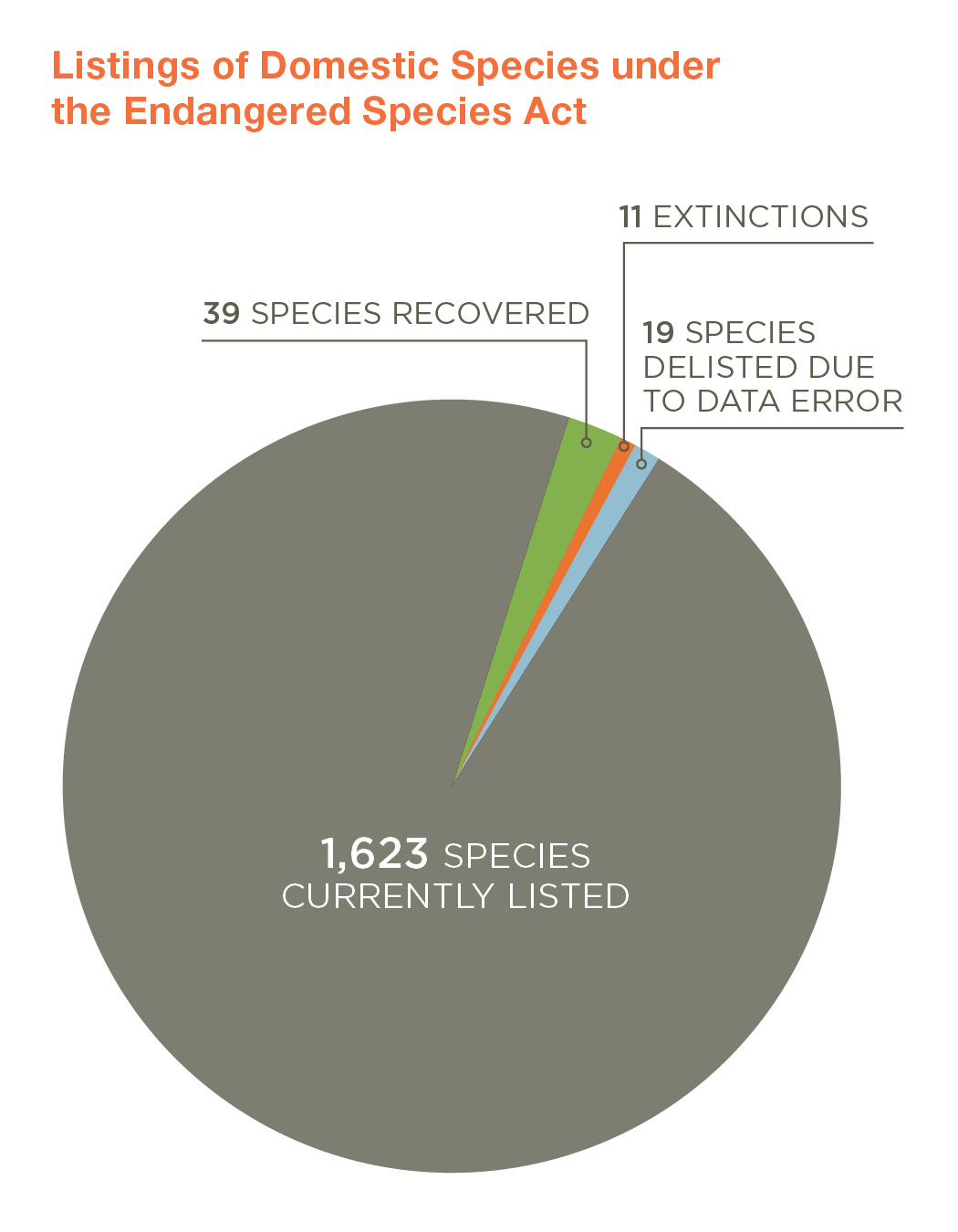

Of the more than 1,600 U.S. species listed during the Endangered Species Act’s 45-year history, the black-capped vireo is only the 41st to recover. This recovery is cause for celebration. But it is also cause for sober reflection. Why don’t we recover more species?

The Challenge

The Endangered Species Act is perhaps the United States’ most powerful and most popular environmental law. Surveys consistently show that more than 90 percent of people support the law, regardless of political leanings. That popularity is easy to understand. Who wouldn’t support the protection of the bald eagle, gray wolf, and polar bear?

The statute has also been extremely successful in one key respect. Almost no species protected by the Endangered Species Act have gone extinct. Ninety-nine percent of the species that have been covered by the act are still with us today. And, in fact, this statistic understates the law’s success in this regard, as several of the species that have gone extinct were likely extinct long before they were listed. The statute’s impressive record of preventing extinction is cause for celebration.

But the statute has failed in another important respect: It has not recovered many species. Less than 2 percent of protected species have achieved that goal. Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming, a medical doctor, has decried this failure, stating that “as a doctor, if I admit 100 patients to the hospital and only three recover enough under my treatment to be discharged, I would deserve to lose my medical license.” In part due to the law’s poor recovery rate and high costs, Congressman Rob Bishop, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, has proclaimed that he “would love to invalidate” the law.

Unfortunately, the widely cited 2 percent recovery rate probably understates the extent to which the statute falls short on this front. The Heritage Foundation’s Rob Gordon recently released a study of the law’s few successes, finding that nearly half of the species that the federal government claims have recovered did not recover because of the law but were instead originally listed by mistake due to bad data.

For example, the Hoover’s wooly star, a plant listed under the act in 1990, was listed based on an initial population estimate of 35,000 to 300,000. After the plant was listed under the act, a full survey was undertaken, which found approximately 135 million Hoover’s wooly stars. Yet in delisting the plant based on this more accurate information, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared that the species had recovered thanks to the act, rather than acknowledging that the original listing was based on a data error.

Despite widespread agreement that the Endangered Species Act should aim to both prevent extinction and promote recovery, the law has been locked in a decades-long political struggle, with each side tossing out their preferred statistic to show that the law is a success or a failure. But few seem to ask: “Isn’t it both?”

Shouting “Stop”

Why has the Endangered Species Act been so successful at preventing extinction but not at promoting recovery? Answering that question can show how the law could be reformed to preserve what it does well while boosting the recovery rate for rare species.

The answer lies in the fundamentally different challenges of achieving these two goals. In many cases, extinction can be prevented by simply shouting “stop!” Where a species is threatened by habitat loss resulting from human development, simply stopping that activity may be sufficient to avoid extinction.

But “stop” is not an effective plan for recovery. As Tate Watkins explains, recovering species can be a costly and difficult effort. That effort requires incentives to encourage and steer those recovery actions. Yet the Endangered Species Act provides weak—or even perverse—incentives for landowners to recover imperiled species.

Fortunately, many people and organizations are intrinsically motivated to contribute to species recovery, without any external incentive. But many more are not so motivated. For them, there must be some reward for devoting resources and energy to recovering species. The challenge, therefore, is to find ways to reform the law to provide those incentives, without sacrificing its effectiveness at preventing extinction.

Tailoring Protections

The Department of the Interior is considering a proposed reform that could preserve the Endangered Species Act’s success at preventing extinction while jumpstarting the recovery of species. It proposes a return to the statute’s original two-step design, under which the restrictions that are applied to species vary based on the degree of threats they face. According to that approach, the act’s controversial “take” prohibition—which forbids any activity that affects a protected species, including activities to recover the species, without a costly and time-consuming federal permit—would be reserved for endangered species and would generally not apply to less vulnerable threatened species.

In “The Road to Recovery: How Restoring the Endangered Species Act’s Two-Step Process Can Prevent Extinction and Promote Recovery,” a recent report published by PERC, I explain that this simple change could have a big impact by better aligning the incentives of landowners with the interests of species.

Regulating endangered and threatened species the same, as we currently do, denies property owners who contribute to the recovery of endangered species any reward for their efforts. When an endangered species’ status is upgraded to threatened, the same burdensome restrictions on land use, for instance, continue to apply.

Under the Interior Department’s proposed reform, however, the take prohibition would act as both a carrot and a stick to encourage recovery efforts. For endangered species, the prospect of lifting the regulation as a species improves would provide a powerful carrot to entice recovery efforts. And, for threatened species, the prospect that a species may continue to decline to endangered status (and thereby trigger the take prohibition) provides an intimidating stick.

Retaining the distinction between endangered and threatened species that Congress originally intended would provide states, conservationists, and property owners much-needed flexibility to develop innovative recovery plans.

This is precisely how Congress intended the take prohibition to work. When debating the bill in 1973, Senator John Tunney explained that by providing a distinction between endangered and threatened species, states would be “encouraged to use their discretion to promote the recovery of threatened species.” “Federal prohibitions against taking,” he continued, “must be absolutely enforced only for those species on the brink of extinction.”

Unfortunately, that two-step listing process—in which threatened and endangered species are regulated differently—was never followed. Instead, shortly after the statute was enacted, the Fish and Wildlife Service issued a regulation that meant endangered and threatened species would be treated the same.

Building on Obama-era Reforms

Recent collaborative conservation efforts undertaken during the Obama administration suggest that a return to the statute’s original design would incentivize collaboration and boost recovery rates.

To avoid the controversial and costly listing of several species, the Obama administration used the Policy for Evaluating Conservation Efforts when Making Listing Decisions, or PECE Rule, to encourage states, conservationists, and property owners to work together to proactively protect species. The logic was straightforward: If stakeholders could develop a collaborative conservation plan that would address the threats to a species, the Fish and Wildlife Service would forego listing the species.

For instance, the rule was used to encourage the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies to develop a range-wide conservation plan for the lesser prairie chicken, a species of grouse found in five western states. That plan coordinates a variety of voluntary conservation efforts, encourages the energy industry to enroll its land in a conservation program, and imposes fees for impacts to habitat. Because the species is principally threatened by habitat fragmentation from human development and encroachment from mesquite trees, the plan has focused on conserving and restoring habitat. More than $63 million in impact fees have been raised, funding conservation easements and the removal of mesquite trees.

Perhaps the biggest test of this approach was the greater sage grouse. With a 165-million-acre range spanning 11 states, the species’ listing would have imposed significant economic burdens on western states. Recognizing these impacts, the U.S. Department of Agriculture launched the Sage Grouse Initiative in 2010, with a goal of conserving the species through partnerships with states, property owners, and conservation groups. Landowner participation was vital because the species relies on wet habitat on private land for forage, especially during the summer. Over the first five years, the initiative enrolled landowners owning 4.4 million acres of habitat and enhanced 400,000 acres by removing invasive plant species. In 2015, the Fish and Wildlife Service announced that the species no longer warranted listing, thanks to these conservation efforts.

Unfortunately, these examples are a rare exception. Conserving species under the PECE rule is difficult because plans must be developed during the short time between when a species is proposed for listing and a final decision is made. For many species, that time will be inadequate to obtain the consensus required, especially when a species has generated substantial conflict in the past.

Environmentalists have also expressed concerns about backsliding. If a species isn’t listed based on anticipated future conservation efforts, will those plans be carried out and prove effective? Foregoing the listing of a vulnerable species entirely, they argue, is a blunt tool.

The Interior Department’s proposed reform would address these concerns. No longer would states, conservationists, and property owners find themselves in a mad dash to agree on a conservation plan in an artificially short window. After a species is listed as threatened, they would have all the time they need to develop the right plan for the species, provided the species does not continue to decline to the point that its status is changed from threatened to endangered.

Environmentalists’ concerns about foregoing species listings would also be solved. A threatened listing would extend several important protections to species. But, by retaining the distinction between endangered and threatened species that Congress originally intended, the reform would provide states, conservationists, and property owners much-needed flexibility to develop innovative recovery plans.

Unleashing States and Conservationists

If the Interior Department follows through on its proposed reforms, states and conservationists should seize the opportunity by incorporating more property rights and markets into species protection. With more flexibility, states can experiment with recognizing forms of property in species and habitat and establish market mechanisms to reinforce them. For instance, for valuable species, states could enable property owners to benefit from preserving species on their land, allowing them to profit from hunting or other uses. For less valuable species, states can provide financial incentives for habitat restoration, as Texas has by paying property owners to remove mesquite trees that encroach on lesser prairie chicken habitat.

Conservationists, too, will have an important role under this reform in promoting property rights and markets as conservation tools. Not only can they contribute expertise on how best to recover species, but they can also provide compensation that reflects the value they attach to species, further encouraging property owners to accommodate species.

For instance, Defenders of Wildlife established a wolf compensation trust that allowed its members, who highly value wild wolves, to compensate ranchers for the costs they bore as the population grew and conflicts between wolves and livestock increased. That program, the group noted, “shift[ed] economic responsibility for wolf recovery away from the individual rancher and toward the millions of people who want to see wolf populations restored” reducing “animosity and ill will toward the wolf.”

Similarly innovative programs are urgently needed to recover each endangered and threatened species. Eric Holst of the Environmental Defense Fund has claimed that cooperative efforts between landowners and environmentalists “are the only approaches” to species conservation “that are likely to work going forward.”

Restoring the Endangered Species Act’s original two-step process will promote those efforts by encouraging landowners to come to the table when a threatened species is identified. And, by giving states and conservationists the flexibility to use property rights and markets to incentivize recovery efforts, this reform will allow more endangered species conflicts to be resolved through mutually beneficial negotiation, rather than fighting them out in the agencies, Congress, and the courts.