In the shadow of Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park, where the mountains rise like an abrupt revelation, the Murie Ranch sits in a peaceful meadow of sagebrush and sticky geranium. The air carries the whistle of wind through lodgepole pines, and on certain autumn mornings, the bugle of a distant elk brings wandering minds and footsteps alike to a stop. It’s a place that feels both grounded and aspirational, a patch where conservation’s past and future share the same wooden porch.

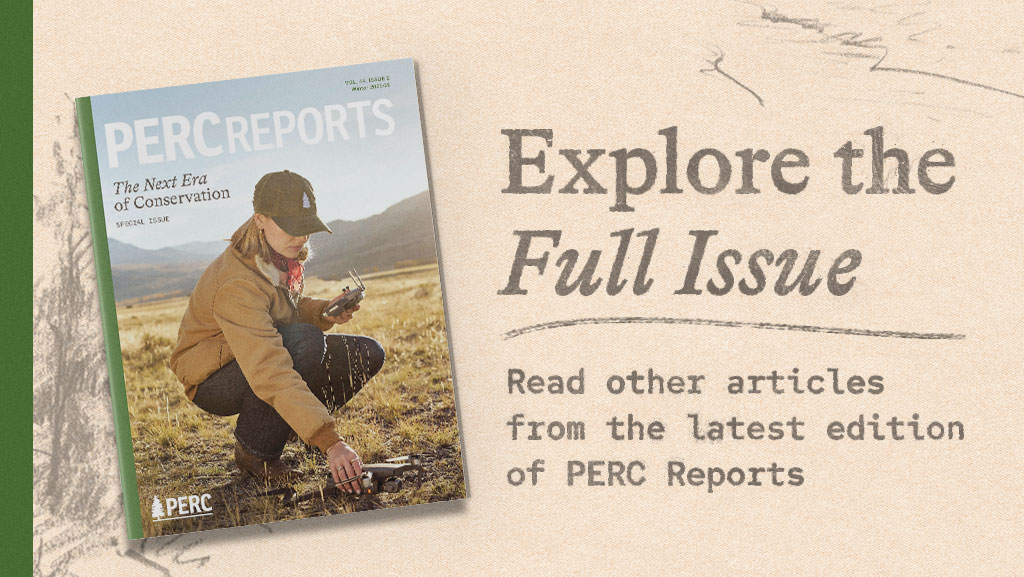

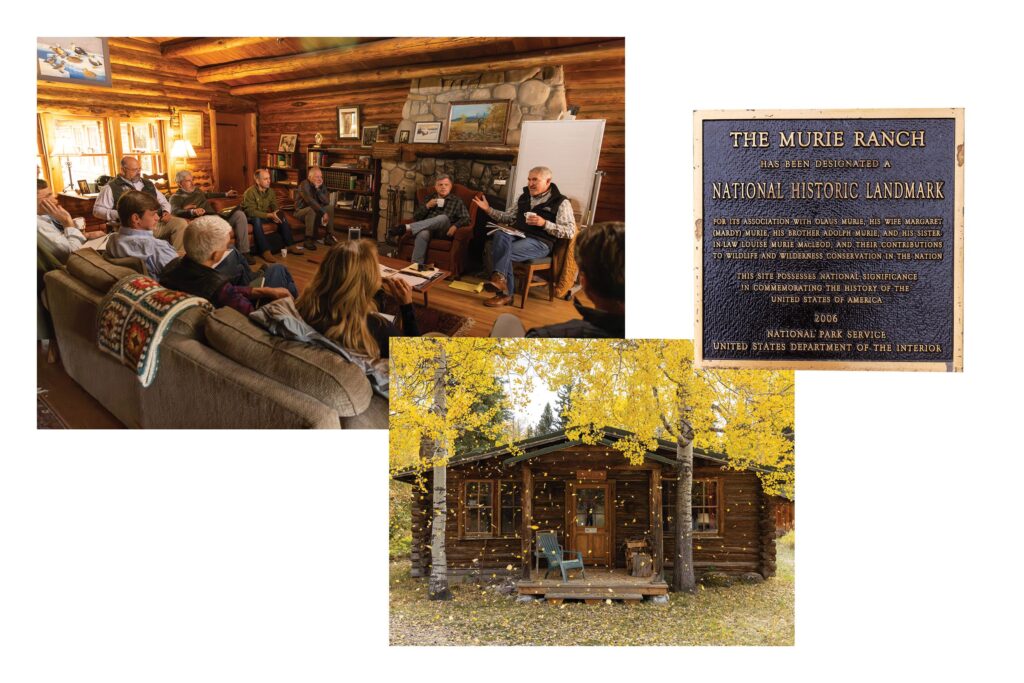

This fall, as PERC convened leaders to imagine the next half-century of stewardship, the ranch offered more than a backdrop. It offered continuity. The small cluster of cabins, worn smooth by decades of comings and goings, tell a story of people who believed that ideas sharpen best in the company of wildness. The Muries—Olaus and Mardy, and Adolph and Louise—made this enclave their home beginning in 1945, transforming what had been a dude ranch into a sanctuary for ecological research and spirited debate.

Long before the ranch became a National Historic Landmark, it was an incubator of conviction. The Wilderness Act of 1964 took shape on its porch, where drafts of the prolific yet imperfect legislation were refined over coffee and conversation. Here, advocates rallied to protect millions of acres in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and presidents, students, and scientists arrived to test their thinking against the clarity of the mountains. What defined the Muries was not grandstanding, but a kind of deliberate humility. They believed that wilderness was best safeguarded by those willing to listen as intently as they spoke.

Olaus sketched wildlife in his studio, using art as a scientific instrument. Mardy, who would later receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom, helped shift the national conversation toward valuing intact ecosystems rather than fragmented ones. Their work shaped the direction of conservation science, but it also shaped a culture—one that prized curiosity, collaboration, and a sense of place.

Today, the ranch is part of the Teton Science Schools campus, where its essence remains unchanged. Elk still wander between the cabins. Black bears still raid berry patches with unapologetic enthusiasm. And people still gather to ask big questions about the future of wild places.

At the Murie Ranch, history isn’t preserved under glass. It breathes. It nudges. It invites. And for those who arrive seeking direction, it offers a silent challenge from history: imagine boldly, act humbly, and let the land guide the way.