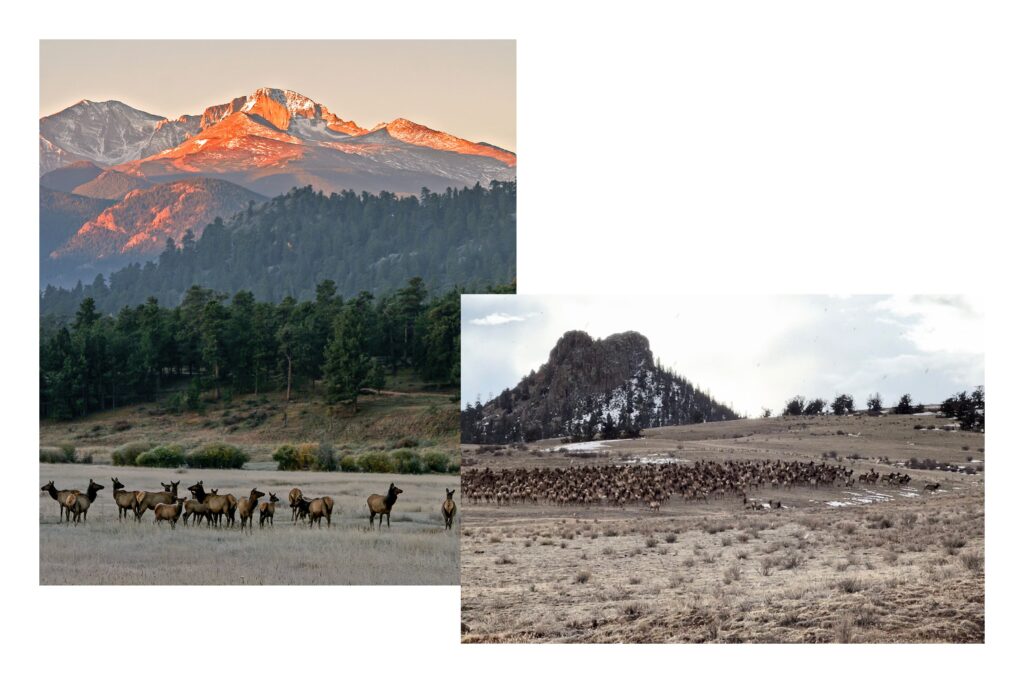

With the sun starting to paint shadows across the front range, I rode side-by-side in an ATV with Dave Gottenborg as he gave me a tour of his high-country ranch in central Colorado. The mosquitoes were thick on my legs as we crossed the stunning working landscape, with Dave pointing out the projects he’s installing and recounting the history of his operation. He’s the PERC partner who spurred Colorado’s first elk migration agreement.

It only takes a second to realize that Dave is a true steward of this landscape—defined by his no-nonsense approach to getting things done and his unquestionable passion for his herd and the landscape that sustains it. He’s the salt of the earth rancher you’d expect from central casting.

But in this alpine wonderland, pressure is growing on Dave.

Elk, once dispersed throughout the region, now find his property an island of calm—animals pushed onto his land by the growing pressure of outdoor recreation on surrounding public forests. Mountain bikers, hikers, and campers increasingly fill those adjacent lands, and with each passing year more elk seek out this landscape where disturbances are few and stewardship is intentional. On Dave’s ranch, the elk can pass through to safety and quiet because of a simple but powerful idea: Conservation works best when it starts with the people who know the land best.

PERC’s migration agreement with the Gottenborg family is a model of the next era of conservation. Rather than relying on top-down mandates, it leans into a bottom-up partnership—compensating landowners for hosting habitat, keeping migration corridors open, and allowing wildlife to move across private lands that have become essential safe havens. Quiet, incremental successes like this rarely make headlines, but they form the backbone of what conservation will become in the coming decades.

For much of the past century, conservation triumphs were framed as federal achievements: sweeping legislation, vast public-land designations, or nationwide species recovery plans. Big on pomp, light on outcomes. But the next 50 years will look different. They will be shaped from the ground up, driven by private landowners, tribal communities, and local stewards whose daily choices cumulatively determine the fate of far more wildlife habitat than any national monument ever will.

More than half of all imperiled species depend on private land. Migration pathways cross working ranches. Rivers flow through backyards and tribal territories. And the men and women who steward these places are not obstacles to ecological success—they are indispensable partners.

The next era of conservation will thrive through secure property rights that give landowners the confidence to invest in habitat, through voluntary agreements that align ecological goals with economic realities, and through tools that reward stewardship, from conservation leasing to market-driven ecosystem payments.

These approaches recognize that durable conservation comes not from coercion, but from cooperation.

Yet the most important shift may be cultural. It’s time to center the people whose choices sustain open space, migration routes, private forests, and pristine rivers. A rancher who keeps grasslands intact for elk, a timber family managing for fire resilience, a tribal community restoring bison—these are not peripheral stories. They are the story of American conservation’s future.

Imagine the landscape 50 years from now: thousands of voluntary partnerships, wildlife corridors stitched together by neighbors instead of regulations, water restored through markets rather than litigation, and forests managed for resilience because landowners are empowered rather than constrained. That future begins with people like Dave Gottenborg—stewards whose quiet work keeps the wild intact.

Conservation’s next era won’t be written up in distant bureaucracies. It will be directly forged on ranches, in watersheds, and across the private lands that quietly hold the key to ecological resilience. It will be conservation from the ground up—rooted in place, guided by people, and scaled through trust.