This special issue of PERC Reports explores the next wave of solutions for our national parks.

In May, the harlequin ducks arrive at LeHardy Rapids in Yellowstone National Park. Sleek, steely-blue birds with slashes and patches of white and a chestnut crown and flank, the males follow their mates to the clear mountain streams where they were born, then breed and depart by the end of the month to molt along the northern shores of Vancouver Island. In the few weeks between when the park’s roads open and the females disappear to nest along the streambank, avid birdwatchers and curious visitors have a slim window of opportunity to spot the continent’s only duck species specialized for fast-moving water leaping in and out of the churning river.

By June, more visitors arrive to search for grizzly and black bears in roadside meadows, wolf pups newly emerged from dens in the Lamar Valley, spawning cutthroat trout, and herds of bison, elk, and pronghorn sheltering knobby-kneed calves. More than half of Yellowstone’s 4.7 million annual visitors (as of 2024) will arrive in the summer months, traversing the high country for cool critter sightings when it is green and lush, and before many of the park’s most iconic wildlife seek shelter from the upcoming winter tens, hundreds, or even thousands of miles away.

For these animals in Yellowstone—and the Florida panthers and roseate spoonbills of the Everglades, the humpback whales of Glacier Bay, the grizzlies in Glacier, Rocky Mountain’s elk, the raptors soaring over Acadia each fall, and many of Big Bend’s nearly 450 observed bird species—America’s national parks provide critical habitat for part of their lifecycle or a segment of their population, but only comprise a portion of the land and resources that these species need to survive and thrive in the long term. As scientific understanding, the threat of development, and public interest all grow, land managers, conservationists, and park enthusiasts alike are figuring out how to support wildlife beyond the borders of national parks, and how to motivate this urgent work.

The Legacy of Monumentalism

There’s no question that wildlife conservation is fundamental to the National Park Service’s mission today, and that the habitat and protection parks provide is critical to many charismatic and lesser-known species. Yellowstone was the cornerstone of wolf reintroduction and bison restoration after federally sanctioned mass extermination drove both to near extinction. Shenandoah National Park’s cool, moist mountaintops shelter the sole population of the endangered Shenandoah salamander in the world. Five species of tiny pupfish persist only in the hot, salty, and isolated waters of Death Valley National Park.

“Parks definitely aren’t enough, even though they are incredibly important,” says Arthur Middleton, one of the nation’s foremost experts on ungulate migration and a longtime champion of large landscape conservation. Middleton, an associate professor of wildlife management and policy at the University of California, Berkeley, and director of the Beyond Yellowstone Program, offers several reasons that parks cannot on their own be expected to support thriving wildlife populations: ”One, they aren’t always in the right places.” For example, no parks protect biodiversity hotspots like the Southeast’s longleaf pine forests or New Mexico’s sky islands. “Two,” he continues, “even the biggest ones are not big enough to sustain some of the most valued wildlife.” The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is 20 million acres, and still the porcupine caribou travel well beyond its boundaries on their annual migration. “Three, there aren’t enough of them and there aren’t going to be enough of them because we’re never going to make a lot more big parks.”

Everglades was the first national park established to protect an ecosystem, rather than a specific scenic or geologic feature.

The reason for this mismatch between what wildlife need and what parks provide is that most parks simply weren’t designed to protect animal populations. Instead, as historian Alfred Runte writes in National Parks: The American Experience, nationalism tempered by economic interests drove the protection and promotion of the West’s most scenic and striking landscapes. Early parks like Yosemite and Yellowstone were established on the back of a young nation trying to prove its worth by measuring the size of its waterfalls against those in the Alps, elevating the antiquity of the redwoods over that of the pyramids, and calling a geyser’s crater a little Coliseum. Proponents of these parks and others only found Congress amenable because the lands were largely considered worthless for settlement, timber harvest, or mineral extraction.

Everglades was the first national park established to protect an ecosystem—in 1947—rather than a scenic or geologic feature, but only the portion of that “river of grass” with the least potential for development was included. Even the sprawling Alaskan parks, which Runte describes as preservationists’ last chance “to design national parks around entire watersheds, animal migration routes, and similar ecological rather than political boundaries,” cannot entirely be called a success. “In park after park,” Runte writes, “critical wildlife habitat had either been fragmented to accommodate resource extraction or excluded entirely.”

“There’s always been experts in or around parks who have noticed this shortcoming,” says Middleton. “There were and are Indigenous societies that have been there since before the parks who are quick to say, ‘Why would anybody have ever expected only this square on the landscape to account for all the important life and relationships that are meaningful about this place?’” Even General Phillip Sheridan, Yellowstone’s first manager, noted that elk and other animals would leave the park in the winter and recommended that Congress expand its borders. But it has taken decades, the growing field of ecology, and most recently, the evolution of GPS tracking and the power to process those data, to more fully and precisely understand the importance of landscape connectivity for nearly all wildlife.

Toward Connection

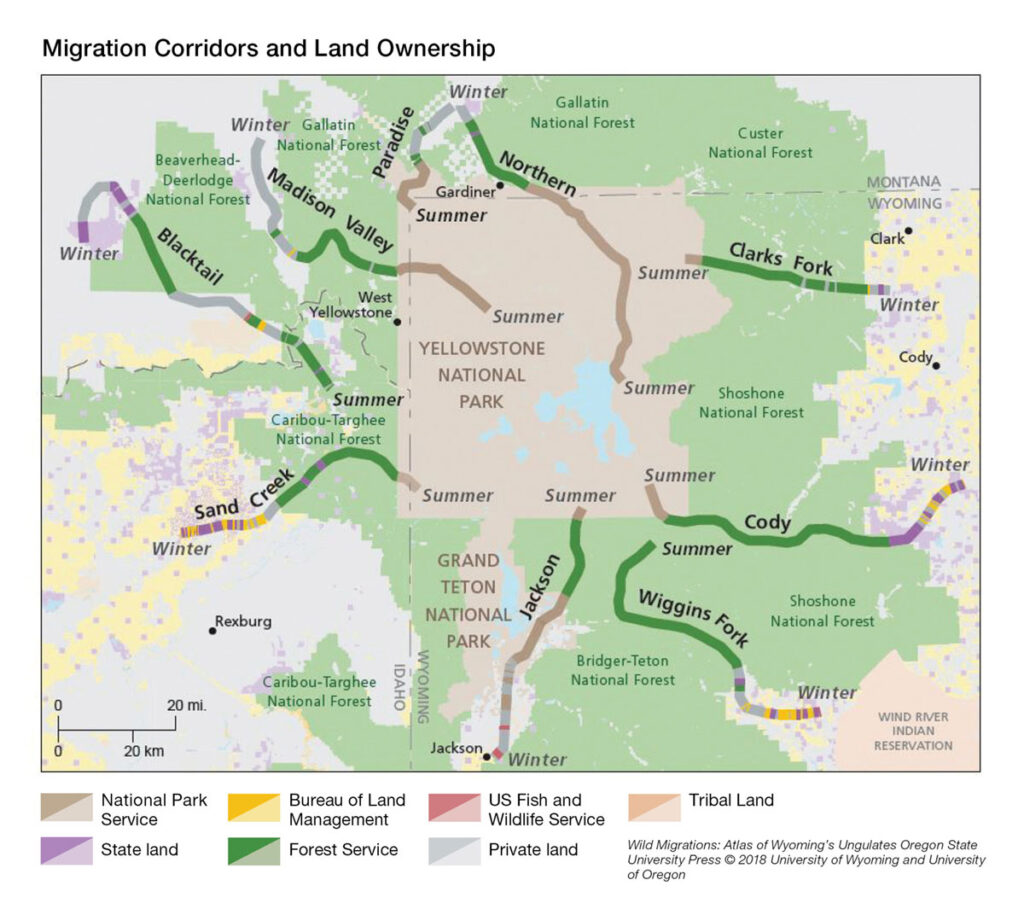

Most obviously, landscape connectivity that spans human-drawn boundaries supports the numerous species that dwell in parks for some of the year but rely on different kinds of habitat or food sources elsewhere during other seasons. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE)—the interconnected matrix of federal, state, Tribal, and private land around Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks—ungulates like pronghorn, mule deer, and elk take advantage of rich pastures within the high-elevation parks during summer and then migrate out of the parks during winter to escape snow and seek higher-quality forage.

They leave in height order, with pronghorn, the shortest and least able to navigate deep snow, departing first, then elk, and eventually the long-legged moose. Some elk make it no farther than private hayfields near Yellowstone or the National Elk Refuge just outside Jackson, whereas the 200-mile “Path of the Pronghorn” from Grand Teton to the Green River Basin is the longest land migration in the contiguous United States. Migratory birds also call parks home for parts of the year, either wintering in the GYE like thousands of trumpeter swans that migrate from Canada, or nesting in the parks like harlequin ducks, bald eagles, mountain bluebirds, yellow warblers, and nearly 100 others.

In a study of 30 radio-collared wolverines in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, researchers found that 80 percent of the individuals’ home ranges extended over three or more major management units, like a national park, national forest, or Bureau of Land Management district. Even more striking is that, unlike many animals who may only use the full extent of their range over the course of an entire year, these wolverines were patrolling nearly their whole range in just a month.

But the field of ecology has shown that landscape connectivity is important for more than just an individual animal’s lifecycle. It’s also essential for maintaining genetic flow between population segments, which helps prevent inbreeding and keeps populations healthier and more resilient to changing conditions. For example, in the decades since a handful of wolves crossed an ice bridge in the 1940s and colonized Isle Royale National Park, the bridge formed less frequently, and gene flow with the mainland was restricted. Faced with a heavily inbred, remnant population of a single male and his one female offspring, managers in 2018 decided to bring 19 Great Lakes Region wolves to the island park. Today, Isle Royale supports 30 wolves in several packs that are successfully reproducing.

Connectivity among populations also makes species less vulnerable to local or global extinction. Consider the Devils Hole pupfish; if a natural disaster or human development wiped out the one pool in the world where it lives—encompassed by a detached unit of Death Valley National Park—the species would be gone forever. In contrast, if there were another pool with a different population connected to it, they could potentially recolonize. Ecologists refer to the minimum viable population as the number of animals needed to weather the potential impacts of environmental, demographic, and genetic changes over time. A 1985 paper in Biological Conservation found that none of the eight largest western national parks were big enough on their own to support the minimum population necessary for the long-term survival of their largest wildlife species.

For many landowners, particularly multi-generational producers, they’re living at the margin, so any additional costs from wildlife really matter.

Hilary Byerly Flint

The implications of these seemingly abstract concepts are real, and at times passionately litigated in the courts and the media. When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delisted GYE grizzly bears in 2017, environmental groups sued, and won, arguing that even though the population had exceeded the stated recovery goal of 500 bears, its genetic isolation from more northern grizzly populations posed a long-term threat that hadn’t been accounted for. Many in the Greater Yellowstone Region accused the Fish and Wildlife Service of moving the goalposts. Last year, Wyoming and Montana relocated two grizzlies from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem to the GYE and renewed calls for delisting, saying that in lieu of natural connectivity between the populations, the states had a demonstrated plan to address concerns over a lack of genetic diversity.

But what about those who want to see grizzlies dispersing into the GYE on their own, or stem the tide of migratory bird decline, or make sure their kids and grandkids can watch bull elk bugling their hearts out against a stunning backdrop of snow-capped Tetons, just like when they were little? “It’s going to take other state and federal lands,” says Middleton, “and private and Tribal lands, all being stewarded well. And there can be something kind of beautiful about that … because it means there is an opportunity for everybody to be part of taking care of a park and helping it fulfill its mission.”

But it needs to happen fast. “There’s just not enough time to screw around,” says Middleton. “There aren’t decades for us to argue and figure out and try to get it just right. We need to act in the next few years, five years, 10 years, to protect some of the best habitat around the parks that’s still not developed.”

The Promise of Private Lands

Subdivisions are one of the worst things that can happen to wildlife habitat, but subdivisions are coming, and it’s partially the fault of our extraordinary parks—because national parks attract development. Temple Stoellinger, a PERC senior fellow and a wildlife law and policy expert from the University of Wyoming’s Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources and College of Law, notes some of the catalysts for recent development near parks. She points to popular TV shows like “Yellowstone” and the ability to work remotely as partial drivers of post-pandemic booms in places like Cody, Wyoming, and Bozeman, Montana. These development booms, she says, are “chunking up winter habitat” for elk, deer, and others. “If you think about the fences being built around each of these 30-acre ranchettes, plus the barking dog, plus the roads to get there, each one is shrinking habitat for wildlife in a critical time of year when they’re already stressed.”

Where such private lands are still intact—say, in the form of a multi-generational ranch—they can provide better habitat for wide-ranging wildlife than public lands. That’s no accident; early settlers, today’s ranchers, and elk in the winter all want the same thing: land along rivers and streams that is more fertile and warmer than the land around it.

Most of these landowners are “really proud to provide habitat for wildlife and enjoy seeing these animals on their land,” says Hilary Byerly Flint, a senior research scientist at the University of Wyoming Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources who led a survey of more than 1,000 landowners who live in mule deer, elk, and pronghorn habitat. “But the large majority of them have also experienced some kind of conflict from having these animals on their property, so it’s costly for them.”

This conflict comes in a variety of forms. Carnivores eat or kill livestock and threaten human safety. Big game compete for forage, damage fences, and can spread diseases to cattle. “For many landowners, particularly multi-generational producers, they’re living at the margin, so any additional costs from wildlife really matter,” says Byerly Flint. “But also, any additional revenue in support of covering those costs can perhaps make a difference.” So, when it comes to conserving the lands around national parks, voluntary, compensated approaches can not only support landowners’ stewardship of wildlife habitat but also keep them financially viable, warding off the ranchettes.

A Growing Toolbox

For federal agencies, state governments, and nonprofits, purchasing conservation easements—deeded restrictions on future development—on agricultural lands is a tried and true l strategy for preserving open space while also supporting the livelihoods of working families and compensating them for the critical wildlife habitat they provide. Easements can be especially useful in areas like the GYE where protecting habitat through land acquisition is difficult because of high land values and, in some cases, resistance to increased federal ownership. And recent programs like the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Migratory Big Game Initiative have helped target the impact of conservation easements further by prioritizing areas within critical big game habitat.

”For a long time,” Stoellinger says, “it felt like conservation easements were the only tool, and that’s just not appealing to everybody.” Permanently giving up development rights, and lowering the value of your land, is a major decision that can reverberate through generations. “Now we’re seeing a more holistic toolbox of how to work with private landowners to improve wildlife habitat or be more tolerant of wildlife on their land,” she says.

In terms of habitat protection, term conservation easements (as opposed to perpetual ones) lower the commitment for landowners to something like 30 years rather than forever. “If even that is too restrictive, shorter-term habitat leases are another option,” says Stoellinger. The Migratory Big Game Initiative used the existing USDA Conservation Reserve Program as a kind of habitat lease, whereby landowners were paid to not develop or farm their land for 15 years.

It’s going to take other state and federal lands, and private and Tribal lands, all being stewarded well. And there can be something kind of beautiful about that.

Arthur Middleton

Moreover, a growing number of private efforts and public programs offer funds to support habitat improvement on private lands. Examples include removing encroaching shrubs from sagebrush, investing in wildfire recovery, managing invasive species, and restoring wetlands and streams. Fence removal or replacement, with wildlife-friendly fencing or even with new, virtual fencing technologies, is another critical component of supporting animal movement in and out of national parks. Wildlife crossings and fish passages also help reduce habitat fragmentation by overcoming barriers to migration.

Finally, conflict reduction can help support private landowners living and working with wildlife outside of national parks at a variety of scales. This may take the form of range riding, livestock carcass removal, improved food storage, compensation for losses, and disease management, either state-run or via emerging models like the East Yellowstone Brucellosis Compensation Fund administered by PERC.

One of the biggest barriers in the GYE, however, is the same one that Stoellinger identified in a survey she led of nearly 50 state and local policies from around the country meant to support landscape connectivity: funding.

Chipping In

The good news is that, despite federal cuts to staffing and funding freezes that have left the delivery of many wildlife conservation and conflict reduction programs in the lurch, “there’s a lot of evidence that people care about nature, and wildlife, and open space,” says Middleton. “They’re showing us with their feet, they’re showing us with their willingness to travel and pay. So there’s got to be ways to convert that into new resources and opportunities for protection and stewardship.”

The National Park Service reported more than 331 million visitors to its 400-plus units in 2024. Grand Teton and Yellowstone combined counted more than 8 million visits. A variety of researchers, think tanks, and both the Montana and Wyoming legislatures have suggested that park visitors could be a valuable source of support for conserving the very wildlife that they are so often traveling to see. In India, for example, visitor fees for tiger reserves help fund conflict mitigation outside of the parks, among other things. No parallel currently exists in the United States.

Byerly Flint, in an intercept survey of nearly 1,000 people in and around Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks published in May, investigated this very idea. 77 percent of respondents reported that viewing wildlife was one of the primary reasons for their trip. The researchers also found that 93 percent of people supported establishing a wildlife conservation fund to collect voluntary donations, 75 percent supported a wildlife conservation tax or fee on goods or services, and 66 percent supported a mandatory wildlife conservation fee.

“Visitors may not always make the connections between the wildlife that they are seeing within the parks and the threatened and fragmented landscape outside the park on which those wildlife depend,” says Byerly Flint, “but it’s clear they recognize a need because they’re willing to pay to support conservation.”

Now we’re seeing a more holistic toolbox of how to work with private landowners to improve wildlife habitat or be more tolerant of wildlife on their land.

Temple Stoellinger

What’s particularly interesting about this study is that Byerly Flint’s team also asked visitors if they were less likely to visit national parks if there were fewer wildlife. Most said yes. “I think it’s no surprise to anyone that wildlife is important to park visitors,” she says. “But to see half of respondents say that they would visit the parks less often if there were fewer wildlife to see, it demonstrates just how critical these abundant and thriving wildlife populations are to park visitation and visitor experience.” Through some widely used economic analyses, the team concluded that not only are people willing to pay to support conservation outside of the parks, but also that loss of wide-ranging wildlife could lead to greater declines in visitation than a fee increase would.

A previous study, led by Middleton, indicated that a moderate fee of less than $10 per entrance, or a sales tax increase of one to two percent in and around Grand Teton and Yellowstone, could generate $10-$20 million annually. That would be enough to provide matching funds for several conservation easements or highway crossings, various human-wildlife conflict mitigation efforts, and the entire annual cost of state compensation for livestock loss to predators in the GYE.

There are, of course, questions and concerns about how any kind of fee or fund would be implemented and how the proceeds would be managed and spent. In particular, there is interest and further research into how fees could be structured such that they don’t disproportionately impact low-income visitors by increasing real or perceived barriers to visitation.

As for all the other ideas and strategies out there for protecting wildlife in and outside of parks, fostering stewardship of the land they rely on, building landscape connectivity, and funding it all, Middleton says, “We need more, not less. We need everybody doing all the things. We need all of it.”