This special issue of PERC Reports features several pilot projects from PERC’s Conservation Innovation Lab. Read the full issue.

The rising sun backlights the ramparts of the Absaroka Mountains to the east as light slips down the Gallatin Range at the western edge of Paradise Valley. A ranch truck pulls into a pasture, and cows and their newly born calves look expectantly at a round bale of hay hanging on the rear. Also looking on with mealtime anticipation is a herd of 20 wild elk. While this scene of mountains, open spaces, ranching, and wildlife at the northern gateway to Yellowstone National Park might appear wonderfully tranquil, it can actually be a recipe for disaster for the rancher and her livelihood—because elk and cattle don’t always mix.

Elk are a keystone species of the Greater Yellowstone region, central to maintaining the ecosystem as well as the tourism and hunting economies. The ungulates typically spend their summers congregating on public land, with Yellowstone at the core. When the weather begins to turn cold, distinct elk herds migrate outward to lower-elevation private working lands. During the winter, many of these elk spend as much as 80 percent of their time on private lands, mostly cattle ranches.

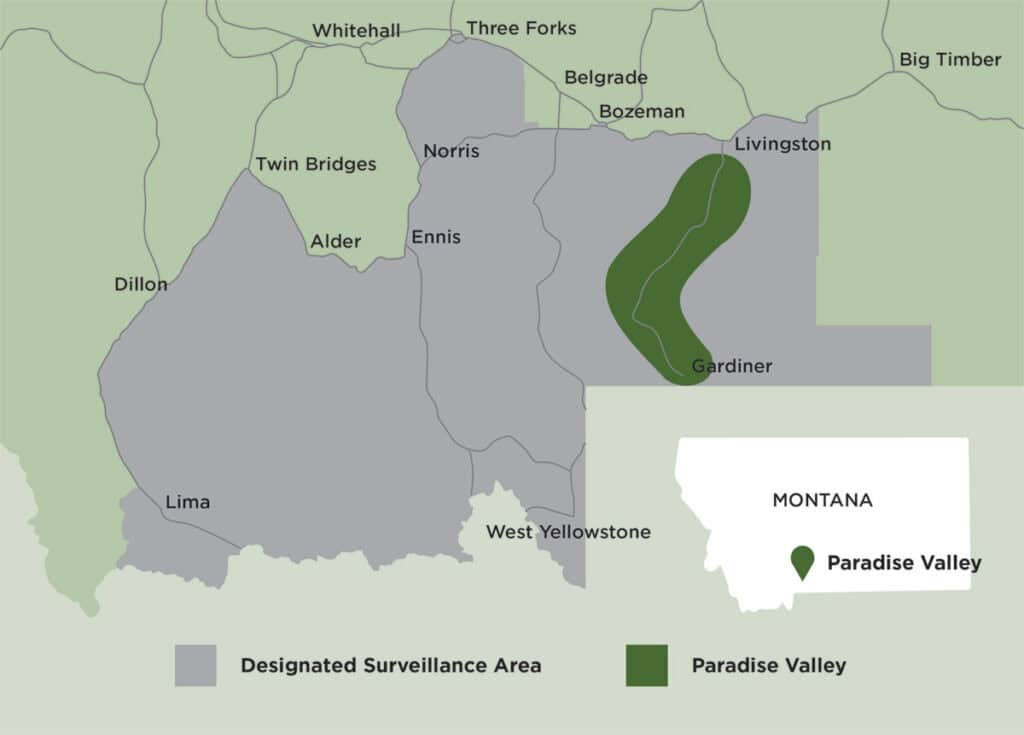

Montana’s Paradise Valley provides critical habitat for several of the region’s elk herds. While these herds are highly valued by many—including tourists, hunters, and other outdoor recreationists—they also bring significant costs and challenges for the valley ranchers who provide forage and security for them. Chief among the concerns: brucellosis, a disease that can be transmitted from elk to cattle, bringing sudden and potentially devastating financial consequences for ranchers.

In exchange for the critical habitat they provide for migrating elk, the fund eases the financial burden area ranchers face due to mandated—and costly—quarantine that results if their cattle contract brucellosis from elk.

Over recent years, PERC has worked with Paradise Valley ranchers to better understand the wildlife challenges they face and to develop new tools that address those challenges. (See “Common Ground” and “Turning Elk Days into Paydays” for other examples.) Through a PERC survey I led in 2019, ranchers in the valley identified brucellosis as the most concerning wildlife issue they face. One local rancher, for instance, told us that by improving habitat for elk, “we’re basically shooting ourselves in the foot because of the increased brucellosis risk.”

We reported the results of our surveys, interviews, and research in a 2020 report “Elk in Paradise,” and PERC helped organize the Paradise Valley Working Lands Group to coordinate conservation actions with landowners. By visiting ranchers and having conversations with them over coffee in their kitchens, we began to understand their challenges and needs. Building these relationships—including plenty of listening—set the stage to create a tool that would help mitigate ranchers’ risk of a brucellosis outbreak.

In January 2023, PERC launched a brucellosis compensation fund for Paradise Valley ranchers, the first of its kind in Montana. In exchange for the critical habitat they provide for migrating elk, the fund eases the financial burden area ranchers face due to mandated—and costly—quarantine that results if their cattle contract brucellosis from elk. The fund is entirely supported by donations from groups and individuals who benefit from the region’s vibrant elk herds. The flexible, private solution not only brings together a coalition of conservationists, hunters, ranchers, and community members to protect elk, but it also helps demonstrate the purpose and potential of PERC’s Conservation Innovation Lab.

Bacterial Burden

Brucellosis is a contagious disease caused by a bacterial pathogen, Brucella abortus, that’s capable of infecting a wide variety of animals, including cattle, bison, and elk. Symptoms of bovine brucellosis include abortion of fetuses, weight loss, and infertility. The disease has significant consequences for animal health and international trade. Brucellosis was once a nationwide scourge, but an eradication program begun in 1934 successfully eliminated the pathogen from most U.S. livestock by the early 2000s. Today, the lone reservoir of B. abortus is the Greater Yellowstone region, where it retains a foothold in populations of wild elk and bison.

Brucellosis was likely introduced to wildlife in Yellowstone National Park in the late 1800s inadvertently by park concessionaires, who grazed dairy and beef cattle to supply milk and meat for guests and employees. Over time, brucellosis became endemic in bison and elk. Eventually, the disease reemerged as a threat to domestic cattle herds as wildlife began transmitting it back to cattle.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of brucellosis in bison and elk is increasing, and its geographic range is expanding. When elk and cattle commingle during the spring migration and calving period, there is heightened risk of transmission. Elk infected with brucellosis shed the bacteria in aborted fetuses and birthing materials. Cattle can subsequently contract the disease from these materials or via soils contaminated with the bacteria. (At present, bison pose little threat of transmission to Paradise Valley cattle due to progress made under the Interagency Bison Management Plan, created in 2000. The cooperative effort, which includes Yellowstone National Park, the state of Montana, multiple Tribal Nations, state agencies, and other parties, aims to ensure spatial and temporal separation between bison and livestock through tolerance zones and other management actions.)

In Montana, the disease is monitored by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the Department of Livestock, and Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. These agencies collectively implement U.S. Department of Agriculture regulations, including developing a brucellosis management plan and establishing a designated surveillance area, or DSA. Cattle producers inside the Montana DSA, which includes Paradise Valley, are subject to more stringent testing, monitoring, and management requirements than the rest of the state and the nation.

In the event a cow tests positive for brucellosis, all livestock in contact with the infected animal must either be sold for slaughter or quarantined on the operator’s property. The process involves frequent testing and strict herd management that can last more than a year. The requirements create significant financial burdens for ranchers; one study estimated quarantine costs for a herd of 400 cattle in the region at nearly $150,000.

The majority of costs related to quarantine are for additional hay. Under normal circumstances, ranchers put up enough hay to feed their cattle throughout the winter, until they can turn out their stock once pastures green up. During a quarantine, however, ranchers are required to hold their cattle in a confined area on their home ground, demanding supplemental feeding of cattle that would otherwise be out on pasture. Another study of bovine brucellosis in the Greater Yellowstone region estimated that 97 percent of costs during a 12-month quarantine were related to feeding.

Combined with potentially ruinous financial loss and added stress to ranching families and cattle alike, the risk of brucellosis reduces ranchers’ willingness to provide vital ungulate habitat. It also has the potential to undermine the future viability of ranching in the region’s large open landscapes.

A Financial Safety Net

Private working landowners in Paradise Valley play a critical role in providing winter and year-round habitat for migratory and resident elk populations. Preserving undeveloped tracts of private land in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is crucial to maintaining the ecosystem’s healthy elk herds. If private working lands are not viable, then subdivision for development and other land conversions will likely accelerate land-use intensity, making habitat conservation more challenging in the future.

The way ranchers steward habitat for elk populations ultimately benefits the broader ecosystem and other wildlife populations. Benefits also accrue to residents, hunters, tourists, and other outdoor recreationists, as well as the businesses that serve them. But sharing one’s private land with elk comes with a cost, particularly for cattle ranchers whose herds can contract brucellosis from infected elk. Consequently, interactions between ranchers and elk can lead to tensions that create challenges to conserving or enhancing wildlife habitat.

Cost-sharing tools, such as a compensation fund, are designed to shift some of the risks associated with brucellosis to third-party groups who value wildlife conservation generally and abundant elk populations specifically. By sharing the costs of providing critical habitat, this approach can increase landowners’ wildlife tolerance, build trust within the community, and help keep working lands working to conserve or enhance habitat and open space.

Reducing ranchers’ financial exposure to disease risk will improve the long-run viability and sustainability of Paradise Valley’s large, private working lands, which play a critical role in sustaining the region’s migration pathways.

Based on a positive response from the ranching community, it became apparent that development of a cost-sharing tool was critical to the future conservation and sustainability of Yellowstone’s elk herds. For one thing, by tracking elk with GPS collars and remote sensors, ecologists helped reveal just how much elk rely on the intact private working lands of Paradise Valley as part of their migratory and winter range. Moreover, brucellosis infection rates have increased in elk populations, and researchers believe that without significant intervention the problem will only worsen, affecting more cattle. Reducing ranchers’ financial exposure to disease risk will improve the long-run viability and sustainability of Paradise Valley’s large, private working lands, which play a critical role in sustaining the region’s migration pathways. No other financial or insurance mechanisms are currently available to private landowners to address the risk of brucellosis transmission.

At the beginning of 2023, PERC launched the Paradise Valley Brucellosis Compensation Fund with financial support from the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Spruance Foundation, and Credova. Based on extensive data collection and modeling as well as interviews and meetings with local landowners, the three-year pilot project has two primary goals: 1) provide a financial backstop to help ranchers weather the storm of a mandatory brucellosis quarantine and 2) demonstrate that the costs of a brucellosis quarantine can be shared by parties interested in supporting and enhancing elk habitat.

Currently capitalized at $115,000, the fund is available to Paradise Valley ranchers and designed to cover 50 to 75 percent of a rancher’s quarantine-related costs following a positive brucellosis test. The partial, cost-share nature of the compensation encourages ranchers to remain proactive and use best practices when taking precautions against the disease. The fund provides a per head, per month payment to help cover the costs—primarily hay—of quarantine. The maximum payout for any one incident is half of the initial fund size, which ensures that the project is not depleted by a single incident.

The fund was intentionally designed to minimize administrative costs by establishing simple procedures, and participation requires no formal enrollment and no direct financial contribution from producers. It relies on state entities for qualification—an official quarantine hinges on an “affected herd” designation by the Montana Department of Livestock—and monitoring. The project also makes payments a simple function of time, number of cattle, and hay price.

To encourage continuation of best practices, producers must meet several basic eligibility criteria. For example, ranchers must adhere to applicable rules associated with operating in the Montana designated surveillance area for brucellosis, including any required vaccination, testing, or management plans. They must also use reasonable methods to prevent livestock from mingling with elk. Fencing of haystacks aimed to prevent elk access is required. And there can be no evidence of a producer intentionally attracting elk to locations with cattle from March to May, the season when transmission is most likely.

To help address the costs of quarantine, the fund is set up to make payouts based on four variables: 1) price of hay, 2) consumption rate of affected herd, 3) duration of quarantine, and 4) season of quarantine. As a pilot, the primary focus is not to cover every unanticipated cost but rather to simply help ranchers keep ranching through a mandated quarantine. The private, nimble nature of the fund renders it flexible, and it can potentially be accessed to cover other associated costs based on a producer’s individual needs.

Innovative Treatment

Ideally, the fund will stand idle during its three-year piloting due to a lack of outbreaks. But history suggests otherwise, and brucellosis remains a serious financial risk for cattle ranchers in Paradise Valley and throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Until now, herd owners have shouldered the full costs of bovine brucellosis. The risk posed by the disease could eventually translate into the loss of ranches and a reduction in available habitat for elk in the area. At a time of rapid regional growth and landscape fragmentation as a result of encroaching development, supporting working cattle ranches by minimizing the impact of brucellosis is a priority for habitat conservation.

PERC’s collaboration with—and listening to—area ranchers produced an innovative means to help them bear the burden of brucellosis risk. If successful, the fund will help lay the groundwork to address similar challenges throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and beyond.