This article was originally published by the Frontier Institute.

While litigation plays an important role in holding the government accountable, it can also be disruptive and warp incentives. As discussed in previous Frontier Institute work, litigation in Montana is threatening forest restoration projects intended to reduce wildfire risk and promote healthy forest ecosystems. This approach of suing to stop projects encourages conflict rather than collaboration, especially where the government pays its opponents’ attorney’s fees.

Litigation has tied the Forest Service in what former chief Jack Ward Thomas described as a “Gordian knot” by limiting the agency’s ability to actively manage national forests. Forest restoration projects are substantially more likely to be litigated than other Forest Service projects, such as trail construction or infrastructure maintenance. But the adverse consequences of litigation are not limited to projects that end up before courts. Forest Service personnel report that the mere risk of litigation can drag out project analysis and consume resources that would be better spent on the ground.

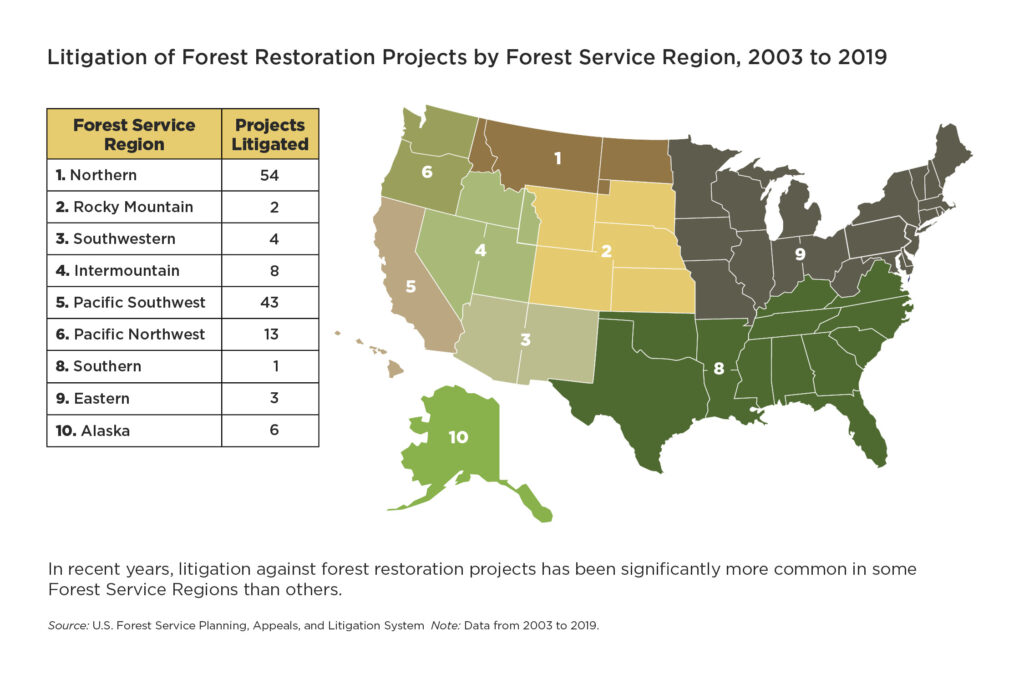

Disruptive litigation adds expense, delays and uncertainty for forest managers, and these consequences are not evenly distributed. For some Forest Service regions or national forest units, litigation is only an infrequent obstacle. Yet for others, it is an ever-present consideration. Litigation is a particularly disruptive factor for national forests within the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals—which has jurisdiction over Montana, Idaho, Nevada and other western states—and near communities with litigious local or special interest groups.

In order to promote forest restoration projects to boost forest health and reduce catastrophic fires, we need to find ways to make litigation less disruptive and clarify how fire risks and forest health should affect injunction decisions.

First, Congress can require lawsuits challenging forest restoration projects to be filed soon after a project is approved. Currently, lawsuits can be filed up to six years after project approval. A shorter deadline would let the Forest Service, private partners and investors know early on whether a project will likely be tied up in litigation, enabling them to better allocate their resources and, perhaps, walk away from the project. While this could provide early confidence to those funding or performing forest restoration, it would not significantly frustrate the ability to bring worthy cases. Many challenges are already filed soon after a project’s approval. And some state equivalents to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) require lawsuits to be filed quickly, without unduly restricting litigation. California’s Environmental Quality Act, for instance, requires many challenges to be filed within 30 days.

A shorter statute of limitations could have the added benefit of spurring greater collaboration by encouraging a project’s critics to develop detailed objections early rather than flyspecking an agency decision after the fact. During the Four Forest Restoration Initiative NEPA analysis in Arizona, for instance, the Forest Service was able to avoid substantial litigation by requiring objectors to articulate their concerns in advance and meet with the agency to discuss them. This allowed the agency to modify the project to address those concerns or prepare a sufficiently detailed explanation of why it declined to do so, increasing the likelihood that the decision would be upheld by courts and reducing the incentive to litigate.

Congress could also make litigation less disruptive by reforming injunctions. Currently, courts can enjoin projects pending the outcome of litigation and, if the challenge is successful, permanently enjoin them until the agency cures the error. This can give litigants a substantial amount of leverage while a lawsuit is going forward, even if the lawsuit is ultimately unsuccessful, because people may be wary of investing in a project when they cannot be certain how long a case will take or what the outcome will be. To provide greater predictability, Congress could expedite cases concerning forest restoration projects by limiting how long preliminary injunctions can remain in place before a court ultimately decides a case.

Ordinarily, when a court determines that an agency has improperly approved some action the proper course is to “vacate” that approval until the agency cures the error. However, Congress can override this rule. Given the substantial risks of doing nothing in areas that are already at high or very high risk of fire and that border populated areas, Congress could impose a heavier burden to justify blocking a forest restoration project in these areas, such as limiting injunctions to cases where moving forward would be objectively unreasonable.

While it is important that people can sue the government to prevent overreach and hold the government accountable, it is also important to increase the pace and scale of our forest restoration work. Reasonable reforms like these are needed to make litigation and injunctions less disruptive and fix America’s forests.