This special issue of PERC Reports examines the Endangered Species Act with an eye toward improving the incentives for species recovery. Read the full issue.

In December 1973, President Richard Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act into law. The new law represented an “important step toward protecting a heritage which we hold in trust to countless future generations,” Nixon proclaimed, explaining that the act “provides the Federal Government with needed authority to protect an irreplaceable part of our national heritage—threatened wildlife.”

Although widely embraced at its passage, the Endangered Species Act has been a source of conflict and controversy ever since. It is arguably the most powerful and stringent federal environmental law on the books. The act explicitly prioritizes the protection and conservation of non-human species and constrains the ability of government agencies to consider trade-offs. Yet for all of the act’s force and ambition, it is unclear that the law has done much to achieve its central purpose: the conservation of endangered species.

The cornerstone of the law is the establishment of a list of “endangered” and “threatened” species. It defines an endangered species as “any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” A threatened species, by contrast, is “any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” Subspecies and distinct population segments may also be listed as endangered or threatened.

The Endangered Species Act’s stated purpose is to “conserve” listed species. As defined by the law, to “conserve” means to use “all methods and procedures which are necessary” to recover species to the point that the law’s protections are no longer needed. This goal may not be realistic for all listed species, particularly those that require ongoing management actions such as predator control, habitat maintenance, or other human intervention. Nonetheless, conservation-as-recovery is what Congress enacted into law.

If a species being listed is akin to being in the emergency room, it is far from a success if the species remains stuck on life support.

The act contains powerful provisions designed to limit government and private actions that could imperil listed species. Under section 7, federal agencies are required to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or National Marine Fisheries Service to ensure that no action “authorized, funded, or carried out” by an agency will “jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species” or destroy critical habitat for such species. As interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1978, this requirement “admits of no exceptions,” and bars federal actions that will imperil the survival of endangered species, “whatever the cost.”

Section 9 of the act prohibits anyone to engage in the unpermitted “taking” of any endangered species. As defined in the act, “taking” not only includes killing, wounding, or capturing an endangered species, but also otherwise harming the species, including by destroying or adversely modifying its habitat. Violators are subject to civil and criminal penalties. Section 10 provides for the granting of “incidental take permits” to authorize activities that would be otherwise prohibited under section 9 pursuant to a government-approved conservation plan.

Conservation via Regulation?

The Endangered Species Act authorizes powerful regulatory tools for species conservation, but do these tools actually conserve species? Despite the federal government’s proclamations of success, the record is not so clear. For the past 50 years, the government has had far greater success at listing species than recovering and delisting them.

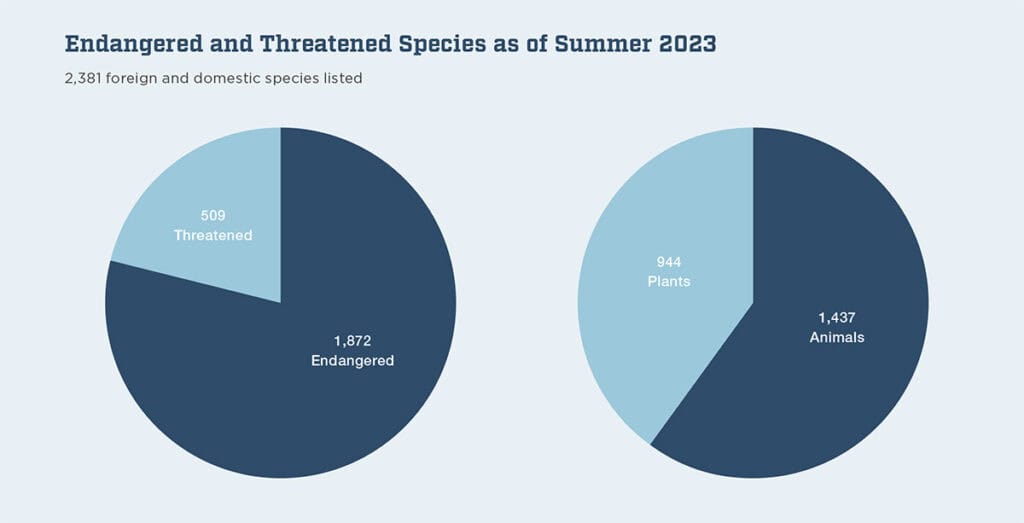

By the end of 1973, there were 124 domestic species on the endangered and threatened lists. As of summer 2023, there were nearly 2,400, including foreign species, which may be listed under the act. Of those listed, nearly 1,900 were considered endangered, and a little more than 500 were threatened. Of the listed species, more than 1,400 were animals and over 900 were plants.

Since enactment, just over 100 species—fewer than 5 percent of those listed—have been delisted, but the Endangered Species Act’s record at recovering species may be even worse than this figure suggests. A species recovering to the point that the act’s protections are no longer necessary is one reason it may be delisted, but it is not the only one. Species may also be delisted because they have gone extinct or because they never should have been listed in the first place, either because they were more numerous than believed or misidentified. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, of the delistings to date, 11 went extinct, and nearly two dozen were originally listed due to data errors. (Scientists estimate as many as 97 additional listed species have gone extinct but have yet to be delisted. A significant percentage of these were likely extinct before they were listed in the first place, and many went extinct before the act’s passage in 1973.)

The federal government identifies 71 species as having “recovered” due to the Endangered Species Act—less than 3 percent of listed species. Yet even this may be giving the act too much credit, as there is good reason to doubt that its regulatory provisions drove successful conservation. While many of these recovered species appear to be doing better than when they were listed, it is not clear federal regulations are the reason. This is certainly true for the 12 foreign species listed as recovered, as the act’s regulatory measures have little if any effect overseas. Nearly two dozen of the other delisted species are plants. These may have benefited from changes in federal land management or active conservation measures inspired by the act, but plant species do not receive the same degree of regulatory protection as animal species. In particular, listed plants are not protected by the same section 9 “take” prohibition as are animals.

Can the Endangered Species Act’s regulations at least take credit for the remaining three dozen-plus domestic animal species listed as recoveries? Not entirely. Because the act allows distinct population segments to be listed, a species may be listed—or delisted—more than once. Thus, the record of recoveries counts two separate listings of the brown pelican and three for domestic populations of humpback whales. The total also includes species that either should never have been listed or recovered for reasons completely independent of the act, including three Pacific Island bird species—the Palau owl, Palau ground dove, and Palau fantail flycatcher—and the American alligator.

The federal government almost certainly deserves credit for successful efforts to preserve raptor species. The American bald eagle, Arctic peregrine falcon, and American peregrine falcon recovered due to limits on hunting and the Environmental Protection Agency’s ban on domestic use of the pesticide DDT. Yet the agency banned DDT in 1972, before the Endangered Species Act was enacted.Where the Endangered Species Act has led to the recovery of endangered species, it has typically been because there was a specific threat identified that could be readily addressed through direct management measures rather than through the act’s primary regulatory provisions. Recovery of the Aleutian Canada goose, for instance, was facilitated by removing predators from nesting grounds, largely on federal lands, and limiting hunting. The Lake Erie water snake was listed as threatened in 1999 and then delisted 12 years later after a public education campaign, improved state land management, and the acquisition of conservation easements helped its population increase by over 80 percent.

Interminable Intensive Care

While the Endangered Species Act’s regulatory provisions may not be recovering many species, it is possible the act is helping prevent extinctions. By some estimates the law has prevented nearly 300 species from going extinct, a significant accomplishment but still well short of the act’s stated goal of recovery. If a species being listed is akin to being in the emergency room, it is far from a success if the species remains stuck on life support.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service’s own biennial status reports to Congress suggest the Endangered Species Act may help some listed species maintain their populations but is improving the condition of relatively few. Between 1990 and 2010, far more species were classified as declining than improving, while even more were classified as stable. The agencies stopped reporting the condition of species in this manner in 2010.

Some defenders of the act argue that it has not had sufficient time to work for the benefit of species. While five decades is a long time, many species have been listed only relatively recently, and Congress rarely provides implementing agencies all the funding the act’s requirements demand. Moreover, not all listed species are capable of a quick recovery, so it is reasonable and foreseeable that many listed species will remain that way for years, if not decades. The recovery plan for the Florida panther, for instance, projects that its population will not be sufficiently large and stable enough to be delisted until 2085.

The Endangered Species Act is more effective on federal land than on private land.

But if the act were working as intended, it would not be so difficult to identify species that have recovered due to its regulatory protections, particularly on private land. Fifty years may be too short to recover all listed species, but it should have been plenty of time to recover more than a handful. According to a recent analysis by PERC, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s recovery plans projected nearly 300 species would have been recovered by now, far more than the roughly 70 recoveries that have actually been achieved.

Habitat loss is the primary threat to endangered species in the United States. At present, most habitat for endangered and threatened species is privately owned. Over two-thirds of threatened and endangered species rely upon private land for some or all of their habitat. Even if all federal lands were managed exclusively for species conservation, it would not be sufficient to save many imperiled species, as a significant percentage are not even found on federal lands. Private land is also often, though not always, ecologically superior to government lands of the same type. If the Endangered Species Act is to be effective at conserving species by preserving their habitats, it must be effective at doing so on private land. Yet that appears to be where the act has been the least effective.

Endangered animal species receive greater regulatory protections than endangered plants, particularly on private land. Yet this does not appear to translate into improved performance. A 2007 study found that listing a species has no positive effect on its status unless accompanied by substantial funding. The same study found that spending on species conservation efforts by land management agencies was more effective than spending by agencies with regulatory authority over listed species. This finding is consistent with prior research showing that the Endangered Species Act is more effective on federal land than on private land.

Endangered species appear less likely to be improving than threatened species, despite the fact that endangered species often receive increased levels of regulatory protection. This could be because endangered species populations were in worse condition than threatened species. But it may also be due to the fact that the act provides less flexibility for endangered than threatened species, and its mandatory strict regulatory measures discourage conservation efforts on private land. On the other hand, a threatened listing may be significant too. According to one recent study, after the lesser prairie chicken was listed as threatened in 2014, employment declined by approximately 1.5 percent in affected counties, with greater declines in counties with more of the bird’s habitat.

Listing a species as endangered imposes strict regulatory measures that effectively penalize landowners who have been successful at cultivating or conserving habitat for the species. Instead of rewarding landowners who have managed lands to preserve habitat for imperiled species, the Endangered Species Act punishes them, reducing land values and constricting permitted land uses.

As economists would predict, if the government penalizes a certain behavior—such as conserving endangered species habitat—it will get less of it. Reports in the 1990s indicated that listing the golden-cheeked warbler resulted in significant habitat loss in Texas. Since then, multiple empirical studies have found that listing species as endangered encourages landowners to preemptively destroy habitat to avoid costly regulatory constraints and discourages participation in conservation efforts.

The Endangered Species Act is a landmark federal law that reflects a profound commitment to the conservation of rare species. Yet after 50 years, there is ample reason to question whether the law is capable of meeting its stated goal of recovering endangered and threatened species. The law’s harsh treatment of private landowners, in particular, must be reconsidered if it is to be effective. The road to recovery for America’s imperiled wildlife will not be paved with punitive regulations alone; getting the incentives right to encourage voluntary habitat conservation on private lands must also become a policy priority if endangered species are to thrive once again.