In 2018, the National Park Service proposed to move its Pacific West Regional Office out of San Francisco, citing the need to save money on rent and salaries in the notoriously high-cost city. There’s an irony in the fact that the city’s high costs prompted the agency to look elsewhere. For more than a century, San Francisco has benefited tremendously from an outdated, bargain-rate lease as the sole user of the dammed Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, which supplies municipal water and generates electricity.

The existential debate over whether the valley should be dammed has largely overshadowed any discussion of whether San Francisco should pay fair compensation for its lease over the property. In a recently published PERC Policy Brief, I argue that Yosemite is saddled with an underpriced and outdated contract for the use of Hetch Hetchy, and I suggest several alternative options that could be used to update the agreement.

Yosemite is the fifth most visited national park in the country—and that visitation has taken its toll. It has the highest deferred maintenance backlog of any national park in the country, with $646 million worth of overdue maintenance projects. The lease over Hetch Hetchy Valley could represent a source of funding to tap for maintaining and preserving public access to the park’s scenic grandeur. Located entirely within the park, the valley provides San Francisco with water as well as approximately one-tenth of the city’s power from hydroelectricity generated by the gravity-driven flow from Hetch Hetchy Reservoir.

In 1913, the Raker Act authorized the unprecedented dam inside the park and also set the fee that the city pays to rent the entire valley in which the dam sits: $30,000 per year. It may be the worst contract in the history of the National Park Service. While the lease price has remained constant over the past century, the value of the valley has not. Yosemite today is exceptionally congested, and restoring the Hetch Hetchy Valley would increase both the quantity and quality of recreational opportunities available to the park’s 4.5 million annual visitors. A benefits-transfer study conducted by a consulting firm has calculated the potential recreational-use value of undamming the valley to be between $1.7 billion and $5.4 billion.

From the nearby urban perspective, the deal to bring water from Hetch Hetchy Valley to San Francisco has been an enormous boon. The city earns about $440 million annually from the sale of Hetch Hetchy water to its own customers and other Bay Area municipalities. San Francisco credits Hetch Hetchy with enabling the city to make a $678 million transfer to its general fund from 1978 to 2001 and providing $151 million of cash-funded streetlights, city-owned solar panels, and similar energy investments. So while the city uses the proceeds of Hetch Hetchy to invest in green infrastructure and streetlights, Yosemite struggles to maintain its roads, treat the wastewater from its visitors, and repair its bridges, buildings, and trails.

Several Options

There is clearly a trade-off between keeping the dam and tearing it down. The former would continue to prevent recreation in the valley, while the latter would force the Bay Area to reassess its entire water supply. What is also clear is that under the current agreement, Yosemite, its visitors, and the American taxpayers who predominantly fund the park are all losing. In light of the situation, the annual lease price San Francisco pays could be adjusted to raise revenue to help maintain infrastructure inside the park, a move that would also be consistent with how national parks structure their concessions and special-use contracts. One of three methods could be used to update the lease between the city and the park and find a more equitable arrangement.

Method 1: Adjust for inflation.

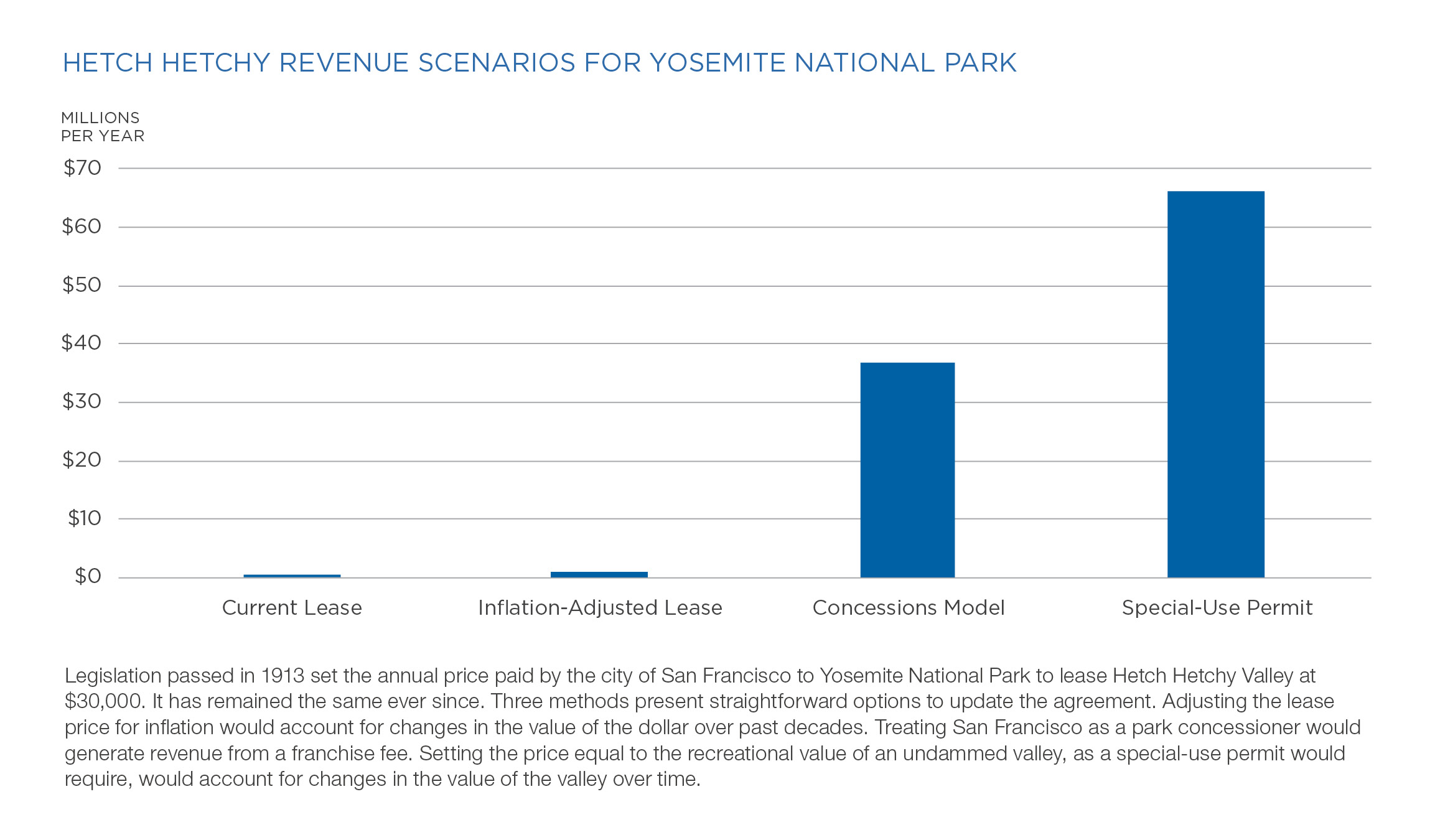

The simplest of the three proposed methods is to adjust the lease price for inflation that has occurred since the passage of the Raker Act. The 1913 fee of $30,000 is equal to approximately $800,000 in 2020 dollars. While this method captures the change in value of the dollar—$30,000 was worth a lot more in 1913 than it is today—it fails to account for the change in value of the valley.

Method 2: Treat San Francisco as a concessioner.

Private companies that offer services to national park visitors are known as concessioners. Concessioners typically pay a franchise fee, which is calculated as a percentage of their gross revenue. While San Francisco may not meet the traditional definition of a concessioner, the model presents a framework to estimate a portion of revenues from the city’s Hetch Hetchy water and power sales that could be used to support Yosemite.

In fiscal year 2017-18, approximately $440 million of San Francisco’s total water sales can be attributed to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Furthermore, electricity sales attributed to the reservoir that year totaled approximately $13 million, meaning that the city generated total sales of approximately $453 million that could be attributed to Hetch Hetchy.

Yosemite National Park has existing concession contracts that use a franchise fee of 8 percent. If San Francisco were treated as a concessioner that paid the 8 percent fee, then the park would receive approximately $36 million annually by allowing the city to benefit from its water resources in Hetch Hetchy.

Method 3: Estimate the annual value of an undammed valley.

The National Park Service is authorized to collect special-use fees for short-term activities—such as memorial services, community events, and weddings—that take place in parks. Such activities are governed by multiple agency rules, but they generally occur when the use provides a benefit to a specific group or individual rather than the public at large and the activity is not legally prohibited in parks. Although the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley was certainly not a short-term event, it resembles a special use in that it does not provide benefits to the general public and is explicitly made legal by legislation. In some respects, the deal resembles a right-of-way permit, a particular category of special-use permit that allows a utility to pass through, under, or over park property.

The National Park Service provides a methodology that could inform an estimate of an appropriate fee for a right-of-way permit for the valley. Agency rules dictate that the fee charged should “reflect the fair market value of the use requested.” In this case, it can be estimated as the annual value of an undammed Hetch Hetchy Valley, which would allow for recreational use. That value has been estimated to be between $1.7 billion and $5.4 billion by consulting firm EcoNorthwest using data on how much visitors value recreating in other areas of Yosemite. Using the low-end estimate of $1.7 billion and a conservative discount rate of 3 percent yields an annuitized value of $66 million, which could be used to set the annual lease price.

Pay the Dam Rent

When the Raker Act passed, its proponents assured the public that the reservoir would bring not only a reliable water source to San Francisco, but also great public enjoyment. As of 2020, however, no bus service or other public transportation exists to access Hetch Hetchy Valley, and appeals to allow boating and swimming in the reservoir have been repeatedly denied. The public road to access Hetch Hetchy needs repair, and in 2016, after four years of drought, San Francisco covered the entire reservoir with floating black balls to protect water quality and reduce evaporation. Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, encompassing 2,000 acres of federal park land, has clearly been maintained for the benefit of San Francisco with minimal consideration of the wider public whose tax dollars—and, in the case of visitors, entrance fees—support the national park.

Yosemite’s current discretionary budget is about $30 million per year, and the park also receives other allocations for special projects and activities and generates additional revenue from sources such as recreation fees and philanthropic donations. A fairer contribution from the park’s largest “concessioner” would greatly benefit the 4.5 million people who visit annually. It’s time to update the century-old arrangement between Yosemite and San Francisco.

Read more in “San Francisco Should Pay Yosemite the Dam Rent,” a new PERC Policy Brief.