Prepared statement before the California Senate Committee on Natural Resources and Water on SB-1175, “Animals: Prohibitions on Importation and Possession of Wild Animals: Live Animal Markets.”

Main Points

- Hunting provides economic incentives and revenue critical to conserving African wildlife in a manner that is self-sustaining and resilient. This includes the conservation of large expanses of habitat and discouraging poaching and illegal wildlife trafficking.

- Hunting and photo-tourism are not interchangeable, and restrictions on hunting have a track record of undermining the conservation of ecosystems and wildlife.

Introduction

Distinguished members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today and provide testimony on the Iconic African Species Protection portion of this legislation. My name is Catherine Semcer, and I am a research fellow with the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC). PERC has a nearly 40-year history dedicated to exploring market and property rights-based solutions to conservation challenges. I am also a research fellow with the African Wildlife Economy Institute located at Stellenbosch University, in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Prior to joining PERC I was part of the leadership team of Humanitarian Operations Protecting Elephants (H.O.P.E.), a non-governmental organization that provides training, advisory assistance, and procurement services to African counter-poaching programs.

In the decades since many African states won their independence, hunting has proven to be an effective, market-based tool to raise revenue and create economic incentives for wildlife conservation and sustainable development. This effectiveness is internationally recognized by respected agencies and institutions including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,[1] the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization,[2] the World Bank,[3] and the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[4] As part of holistic conservation programs, hunting enables African nations to practice conservation at landscape scales while improving the lives and livelihoods of rural and indigenous peoples in a way that reduces dependence on foreign aid and philanthropy.

Recent U.S. restrictions on the importation of certain hunting trophies have had negative consequences for African wildlife conservation and produced no discernable, substantive benefits. Enshrining and expanding such bans in law risks seeing these negative consequences metastasize over a wider area, especially if no economically viable alternatives to hunting are present or provided. For these reasons, the legislature should proceed with a high degree of caution before taking any action that would further undermine the ability of African nations to use hunting as part of their conservation and sustainable development programs.

My testimony will explain some of the benefits hunting currently provides; why the practice is not easily replaceable with other forms of tourism; the known costs of existing U.S. restrictions on hunting trophy imports from African nations; and the anticipated costs should those restrictions be expanded by this legislature.

Hunting provides economic incentives and revenue necessary to conserve African wildlife in a manner that is self-sustaining and resilient.

The principal conservation benefits of hunting in Africa are the creation of economic incentives to conserve wildlife habitat and healthy wildlife populations. The potential of revenue generated by hunting transforms wildlife and habitat into economic assets for individuals and communities and allows hunting to be competitive with other land-use options. Additional benefits include rural job creation and the generation of revenue for conservation agencies that in turn decreases their dependence on foreign aid, philanthropy, and appropriations from central authorities.

Approximately 20 African nations use hunting to achieve their conservation goals. As of 2007, hunting areas in Sub-Saharan Africa were estimated to conserve approximately 344 million acres of wildlife habitat. This figure exceeds the total size of the region’s national parks by 22 percent. For further perspective, hunting areas in Sub-Saharan Africa are more than 6.5 times the size of the U.S. National Park System, roughly three times the size of the U.S. National Wilderness Preservation System, and more than twice the size of the U.S. National Wildlife Refuge System.

Africa’s hunting areas are a mixture of public, indigenous, and private lands. Many of these lands are remote and generally considered to be marginal and sub-marginal. Hunting has provided a means by which these lands can be used to generate revenue and other benefits without converting them to agriculture. Such conversions would degrade the areas’ ability to function as wildlife habitat for lions and other key species. It is worth noting that there is a growing consensus that such conversion can also be a precursor of pandemics like the one we are currently experiencing.[5]

As has been noted by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), worsening land degradation has reached a critical point worldwide and is driving species extinctions and undermining the long-term well-being of two-fifths of humanity. The expansion of croplands and grazing lands, as would likely occur in hunting areas absent hunting programs, is a key driver of this degradation. The IPBES identifies avoiding degradation as the most cost-effective strategy to maintain the ecosystem services that underpin larger economies.[6]

The primary economic incentives for habitat conservation are derived via revenue-sharing agreements between rural communities, private enterprise, and conservation agencies and from direct payments to private landowners. For example, in Zimbabwe, under the Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE), rural communities lease hunting and other tourism rights to commercial outfitters. The communities are then paid 50 percent of the revenues generated by the tourism activity. These revenues are required to be redirected to wildlife conservation and community development programs.

This arrangement has incentivized the conservation of 12 million acres of wildlife habitat in Zimbabwe and benefited 777,000 households. Hunting accounts for 90 percent of the revenues raised, which totaled approximately $11.4 million between 2010 and 2015. Elephant hunting provides 65 percent of these revenues, with 53 percent of those coming from American hunters.[7]

While the CAMPFIRE program is not perfect and would benefit from increased international engagement and transparency, it has produced positive results for wildlife, especially elephants.[8] The incentives for wildlife and habitat conservation provided by the CAMPFIRE program are a significant contributing factor to Zimbabwe being home to the second largest elephant population in Africa, according to the IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group. Currently numbering more than 82,000 animals, Zimbabwe’s elephant population is a success to celebrate, not punish by restricting its ability to use the tool that delivered that success.[9]

In South Africa, where almost all of the land is in private ownership, access to the U.S.hunting market has created incentives for farmers and ranchers to convert agricultural lands back into wildlife habitat. At present, approximately 50 million acres of private ranchlands in South Africa are being primarily managed for wildlife. These lands contain approximately 12 million head of free-ranging game, twice the number found in South Africa’s national park system. This management for wildlife allows these landowners to collectively generate approximately $1.6 billion in income each year from the sale of hunts and game meat derived from those hunts.[10]

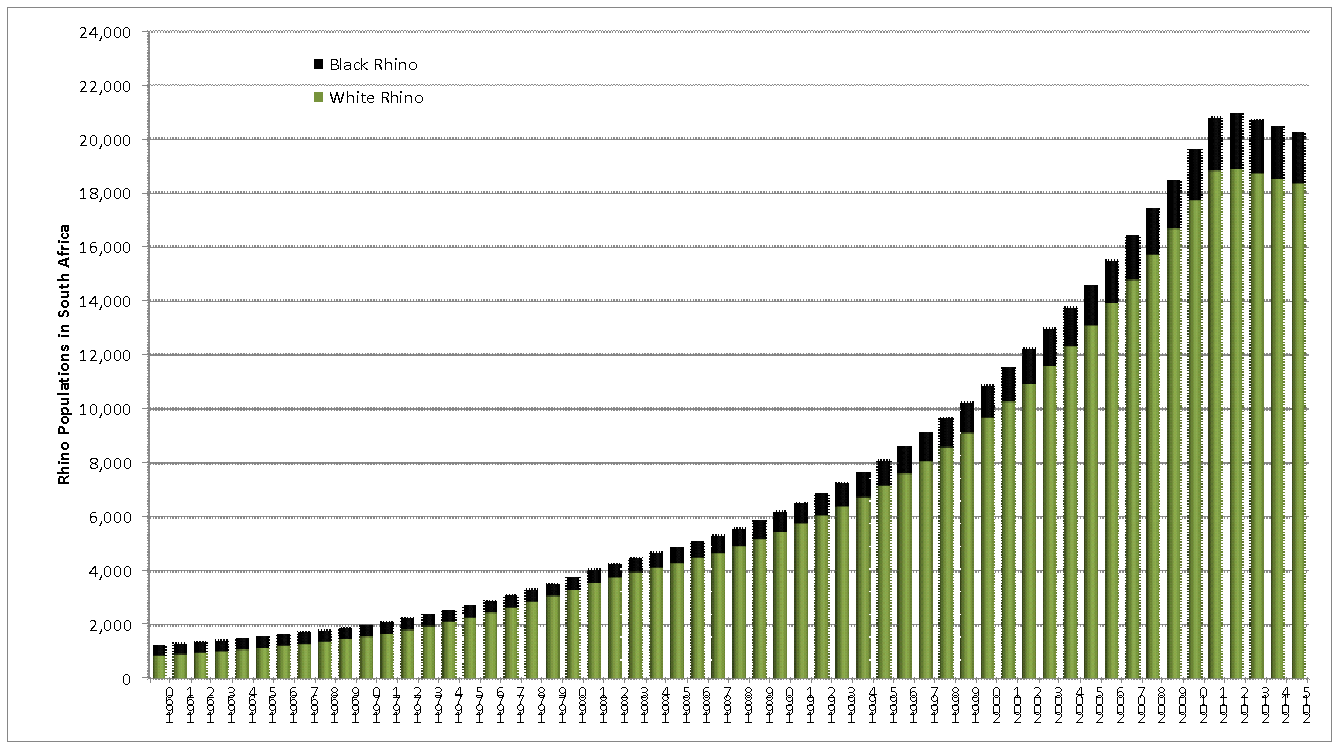

One species that has been brought back from near extinction as a direct consequence of this system is the southern white rhino. In 1960, South Africa’s population of this species numbered only 840 animals, and hunting them was illegal. By 1968 the population had increased to approximately 1,000, and hunting of the species was reopened. The size of the market for rhino hunting and the profits that could be generated led South African landowners to intentionally populate their land with rhinos, as well as breed them to the point that their number has now increased to more than 18,000[11] (See Figure 1). This conservation effort, driven by financial incentives derived from hunting, has made South Africa home to 93 percent of the world’s remaining white rhinos.[12]

Other rare and iconic species that have benefited from hunting on private lands in South Africa include the Cape Mountain zebra, currently being considered for delisting under the US Endangered Species Act[13] and bontebok. In the case of the Cape Mountain zebra, the species has recovered from a population of approximately 100 animals in the 1950s to over 4,800 animals today.[15] Similarly, bontebok have recovered from a total population of 17 animals in the 1930s to between 2,500 and 3,000 animals because of the habitat and other conservation efforts provided by South Africa’s private hunting reserves.[16]

Figure 1[14]

The wildlands conserved via hunting do not just secure a future for well-known species like rhinos and zebras, they also provide habitat for countless birds, insects, small mammals, reptiles, and fishes. While these creatures are often ignored by hunters and photo tourists alike, they collectively form a much greater share of the world’s biodiversity than the large mammals that draw millions of visitors to Africa each year. These “little things that run the world” should not be overlooked in the ongoing public debate around hunting.

South Africa’s private hunting reserves have been instrumental in averting the extinctions of the geometric tortoise and Waterberg copper butterfly. In Tanzania’s Kilombero Valley, a key wildlife corridor between the Selous Game Reserve and Udzungwa Mountains, hunting revenues provide economic incentives to keep wildlands intact that provide habitat for the Kilombero weaver, Kilombero susticola, Kilombero white-tailed sisticola, and Kilombero reed frog, all of which are endemic to the area. In Mozambique’s Coutada 11, a hunting area nearly half a million acres in size, scientists have discovered a species of mole rat, Cryptomis bierai, they believe may be taxonomically distinct. More discoveries like these likely await in Africa’s hunting areas, but for them to be appreciated by science and by those who benefit from the services healthy ecosystems provide, the habitat these areas protect must be kept intact.

Estimates of the cash revenue generated by hunting in Africa vary between $190 million and $326.5 million annually, with the latter figure accounting for all in-country expenditures.[17] Researchers who calculated the latter figure also calculated that the value-added contribution to GDP is $426 million and that the hunting sector supports 53,400 jobs.[18]

This revenue has been criticized as being insignificant in relation to tourism’s total contributions to GDP and in proportion to the amount of land managed for hunting.[19] These critiques, however, ignore key contexts. For example, even at the lower end of the estimated revenue generation, revenues from hunting are still almost one-third higher than the $142 million generated by protected area entrance fees in 14 African countries that were surveyed.[20]

While critics argue that the number of jobs created by hunting are low in comparison to the overall labor market, such criticism neglects that areas where hunting occurs typically have low human population density with small labor pools. At the local level, where there can be fewer than 1,000 households, the job creation resulting from hunting is significant.[21]

It is a fact that conservation is next to impossible absent a supply of capital. Hunting revenues, while relatively a small contributor to overall GDP, have a disproportionate impact on the budgets of agencies and parastatals responsible for wildlife conservation, providing them with significant portions of their operating budgets.

One case in point is the Tanzania Wildlife Management Authority, which receives 60 percent of its income from hunting license fees.[22] In the Selous Game Reserve, where hunting is allowed, 50 percent of hunting revenues are reinvested into conservation generally and anti-poaching specifically.[23] These arrangements are similar to those we employ in the United States, where state wildlife agencies are partially funded through the sale of hunting licenses and permits.

Finally, the exclusive focus of critics on cash revenues and related economic impact ignores the added value hunting provides rural communities, especially in relation to food security. In Zambia, for instance, researchers with the University of California, Los Angeles and Mississippi State University estimate that hunting annually provides more than 286,000 pounds of meat to rural communities adjacent to hunting areas. They estimate this meat is valued at $600,000 per year.[24] The committee should note that there are no documented links between the consumption of the game meat provided by hunting and increased risk of pandemic disease.

Hunting and photo-tourism are not interchangeable, and restrictions on hunting have a track record of undermining the conservation of ecosystems and wildlife.

Hunting and photo-tourism are not interchangeable. While photo-tourism generally occupies a larger share of African tourism economies than does hunting, ongoing energy and infrastructure development projects in African national parks illustrates that photo-tourism is not superior to hunting in terms of providing incentives for conservation in contemporary Africa.

Photo-tourism is also not inferior to hunting. Rather, the two are critical partners in generating public interest, capital, and economic incentives to conserve African ecosystems and wildlife. Working in concert they help to deliver wildlife and ecosystem conservation at a landscape scale in ways that leverage the relative economic viability of each activity in a given place. Hunting is well suited to conserve remote areas that are less scenic and lack the infrastructure and wildlife population densities that typically characterize national parks and other areas best suited for photo-tourism.

For example, analysis conducted in Botswana concluded that hunting was the only economically viable wildlife-dependent land use on two-thirds of the country’s wildlife estate.[25] Other researchers have concluded that only 22 percent of the country’s Northern Conservation Zone has intermediate to high potential for photo-tourism.[26]

A 2016 study published in Conservation Biology also determined that if hunting were removed from the uses available to wildlife conservancies in Namibia, 84 percent of them would become financially insolvent. This insolvency would place an area of habitat five times the size of Yosemite National Park at risk. The same study also found that if photo-tourism was removed as a revenue stream, only 59 percent of wildlife conservancies would remain economically viable.[27]

The interdependence of hunting and photo-tourism in African conservation makes increasing barriers and restrictions on the former something that should be undertaken with extreme caution and only after economically viable alternatives have been identified, designed, and funded.

The impacts of imposing such barriers and restrictions are well documented. Following Kenya’s complete ban on big-game hunting in the country, it has seen declines of between 72 percent and 88 percent in species that are relatively common in countries that allow hunting. These include warthog, lesser kudu, Thomson’s gazelle, eland, oryx, topi, hartebeest, impala, Grevy’s zebra, and waterbuck. Many of these declines can be attributed to the conversion of wildlife habitat to use by livestock.[28]

Following the U.S. ban on elephant trophy imports from Tanzania and increased restrictions on lion imports under the Endangered Species Act, more than 6 million acres of hunting blocks were surrendered back to the government due to decreased booking by American hunters and hunting having lost its economic viability as a land use in these areas. The surrender of these areas was accompanied by the dissolution of a 100-man counter-poaching unit that had been employed by a hunting outfitter.[29]

Researchers with the University of Pretoria have lent credence to the Tanzanian experience, determining that if just lion hunting were to end in the nations of Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia, nearly 15 million acres of wildlife habitat managed as hunting blocks would see decreased economic viability as wildlife habitat.[30]

Conclusion

The United States currently represents more than 70 percent of the global market for hunting trophies[31] and the ability of African hunting programs to conserve habitat, as discussed above, depends on their being able to access the US market. This legislation will create and expand barriers and hurdles to market participation by US hunters that can reasonably be expected to result in an overall decrease in market participation.

Such decreased participation risks undermining the economic viability of hunting as a conservation tool at a time when threats to habitat and the full range of species that depend on it are increasing, and all available conservation tools should be being utilized to arrest current trends. This is especially true when no economically viable alternatives to hunting are present in the market.

For this reason, the legislation, as written, will likely fail at accomplishing its stated goals and we recommend that the legislature develop and pursue an alternative policy course. Thank you.

[1] E.g., Black Rhino Imports from Namibia. Accessible at https://www.fws.gov/international/permits/black-rhino-import-permit.html.

[2] Baldus, R.D., Damm, G.R. & K. Wollscheid (eds.): Best Practices in Sustainable Hunting – A Guide to Best Practices From Around the World. 2008. International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation and United Nations Food and Agriculture Program

[3] World Bank Group. Mozambique Conservation Areas for Biodiversity and Development Project. Accessed at http://projects.worldbank.org/P131965?lang=en July 13, 2019

[4] International Union for Conservation of Nature. Informing Decisions About Trophy Hunting. Briefing Paper. September 2016.

[5] See e.g. J. Vidal. March 18, 2020. Destroyed Habitat Creates the Perfect Conditions for Coronavirus to Emerge: Covid-19 May be Just the Beginning of Mass Pandemics. Scientific American. Accessible at

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/destroyed-habitat-creates-the-perfect-conditions-for-coronavirus-to-emerge/

[6] IPBES (2018): The IPBES Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration. Montanarella, L., Scholes, R., and Brainich, A. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 744 pages, and World Bank. 2019. Tanzania Country Environmental Analysis – Environmental Trends and Threats and Pathways to Improved Sustainability. World Bank. Washington, DC.

[7] CAMPFIRE Association. 2016. The Role of Trophy Hunting In Support of the Zimbabwe CAMPFIRE Program. CAMPFRE Association. Harare, Zimbabwe

[8] Tchakatumba, P.K., Gandiwa, E., Mwakiwa, E. Clegg, B. and S. Nyasha. 2016. Does the CAMPFIRE Programme Ensure Economic Benefits From Wildlife to Households in Zimbabwe? Ecosystems and People. 15(19): 1

[9] C.R. Thouless, H.T. Dublin, J.J. Blanc, D.P. Skinner, T.E. Daniel, R.D. Taylor, F. Maisels, H. L. Frederick and P. Bouché. 2016. African Elephant Status Report 2016: an update from the African Elephant Database. Occasional Paper Series of the IUCN Species Survival Co

[10] Wildlife Ranching South Africa. Wildlife Ranching in South Africa. Undated Presentation. Accessible at https://www.myewa.org/pdf/WRSA-EWA-Presentation.pdf

[11] 7 T’Sas-Rolfes, M. 2011. Saving Rhinos: A Market Success Story. PERC Case Study. Accessible at https://www.perc.org/2011/08/19/saving-african-rhinos-a-market-success-story/

[12] Van Norman, J. Undated. Protecting Africa’s Last Rhino Population’s from Poaching. US Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessible at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/news/episodes/bu-Fall2013/story5/index.html

[13] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. April 16, 2018. Service to move forward with petition to delist cape mountain zebra, retains ESA protections for Preble’s Meadow jumping mouse. News release accessible at https://www.fws.gov/news/ShowNews.cfm?ref=service-to-move-forward-on-petition-to-delist-cape-mountain-zebra-r&_ID=36255

[14] Based on figures from the IUCN Rhino Specialist Group

[15] For a full discussion see: Conservation Force. May 10, 2017. Petition to Delist, or in the Alternative to Downlist, the Cape Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra) From the Endangered Species List. Accessible at https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FWS-HQ-ES-2017-0100-0003

[16] M.L. Miller. July 8, 2015. Bontebok Can’t Jump: The Most Dramatic Conservation Success You’ve Never Heard About. Accessible at https://blog.nature.org/science/2015/07/08/bontebok-cant-jump-the-most-dramatic-conservation-success-youve-never-heard-about/

[17] Booth, V.R. 2010. The Contributions of Hunting Tourism: How Significant is This to National Economies? In Contribution of Wildlife to National Economies. Joint Publication of FAO and CIC. Budapest, Hungary

[18] Southwick Associates. 2015. The Economic Contributions of Hunting Related Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa. Accessible at https://www.southwickassociates.com/economic-contributions-of-hunting-related-tourism-in-eastern-and-southe rn-africa/

[19] Murray, C. K. 2017. The Lion’s share? On the Economic Benefits of Trophy Hunting. A Report for the Humane Society International, prepared by Economists at Large, Melbourne, Australia.

[20] World Bank Group. 2018. Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods Through Wildlife Tourism. World Bank. Washington, DC

[21] Tchakatumba, P.K., Gandiwa, E., Mwakiwa, E. Clegg, B. and S. Nyasha. 2016. Does the CAMPFIRE Programme Ensure Economic Benefits From Wildlife to Households in Zimbabwe? Ecosystems and People. 15(19): 1

[22] Estes, R. 2015. Hunting Helps Conserve African Wildlife Habitat. African Indaba. 13:4

[23] International Union for Conservation of Nature. Informing Decisions About Trophy Hunting. Briefing Paper. September 2016

[24] White, P.A. and Belant, J.L.. 2015. Provisioning of Game Meat as a Benefit of Sport Hunting in Zambia. PLOS One. 2015. 10:2.

[25] Barnes, J. 2001. Economic Returns and Allocation of Resources in the Wildlife Sector of Botswana. South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 31: 141-153

[26] Winterbach, C.W., Whitesell, C. and M.J. Somers. 2015. Wildlife Abundance and Diversity As Indicators of Tourism Potential in Northern Botswana. PLoS One. 10.

[27] Naidoo, R., Weaver, L.C., Diggle, R.W., Matongo, G., Stuart-Hill, G. and C. Thouless. 2016. Complimentary Benefits of Tourism and Hunting to Communal Conservancies in Namibia. Conservation Biology. 30:3

[28] Ogutu, J.O., Piepho, H.P., Y Said, M. and G.O. Ojwang. 2016. Extreme Wildlife Declines and Concurrent Increase in Livestock Numbers in Kenya: What Are the Causes? PLoS One. 11.

[29] E. Pasanisi. Personal Communication. 2018.

[30] 3 Lindsey, P.A., Balme, G.A., Booth, V.R. and N. Midlane. 2012. PLoS One 7(1).

[31] Killing for Trophies: An Analysis of the Global Trophy Hunting Trade. International Fund for Animal Welfare. 2016. Accessed July 13, 2019 at https://s3.amazonaws.com/ifaw-pantheon/sites/default/files/legacy/IFAW_TrophyHuntingReport_US_v2.p df