Prepared statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources’ hearing to examine deferred maintenance and operational needs of the National Park Service on April 17, 2018.

Summary

- Congress has prioritized the acquisition of new parks over the care and maintenance of existing parks. Since 2000, 35 park units have been added to the National Park System without corresponding increases in appropriations. As a result, the National Park Service’s deferred maintenance backlog has grown to $11.6 billion while the agency’s budget has been stretched thinner and thinner.

- Although Congress has granted parks the authority to retain recreation fees, the National Park Service has often restricted the ability of local park managers to use those receipts to effectively address the maintenance challenges and operational needs that matter most to visitors.

- Local managers know best how to address their maintenance and operational challenges. The Secretary of the Interior has emphasized the importance of putting more decision-making authority in the hands of local managers rather than distant bureaucracies in Washington, D.C. Congress could help by clarifying the authority of local park managers to fund critical maintenance or operational challenges from fee revenues without further restrictions and red tape from Washington.

- Conservation, at its core, is about preserving and maintaining what you already own. Reducing the deferred maintenance backlog should be a top priority, but the more fundamental challenge is to prioritize the routine or cyclic maintenance that is necessary to prevent maintenance projects from becoming deferred in the first place.

Introduction

Chairman Murkowski, Ranking Member Cantwell, members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you to provide testimony on the deferred maintenance and operational needs of the National Park Service. My name is Shawn Regan, and I am a research fellow and the director of publications at PERC—the Property and Environment Research Center—a nonprofit institute in Bozeman, Montana, where I study public land policy and conservation issues.[1] PERC is the nation’s leading organization dedicated to exploring market-based solutions to environmental problems.

The topic of this hearing is directly related to my research at PERC, but it is also important to me personally. For four years, I worked as a backcountry ranger for the National Park Service in Olympic National Park, where I regularly assisted and informed park visitors, monitored and maintained the park’s resources, and ensured visitor safety and compliance with park policies. During my time working for the Park Service, I witnessed first-hand the maintenance and operational challenges the agency faces, from dilapidated transportation infrastructure and outdated visitor facilities that undermine the visitor experience to the operational shortfalls and excessive red tape that hamstrings the agency and limits its ability to sufficiently carry out its mission.

In short, today I will provide my perspective on how the National Park Service has become burdened by an $11.6 billion backlog of deferred maintenance and why Congress and the Park Service have so far been unable to significantly reduce that backlog. I will offer some ideas on how Congress and the agency can effectively address the backlog problem. In particular, I will explore ways to enable local park managers to better address the maintenance and operational needs that matter most to visitors, and I will emphasize that Congress should focus on the critical maintenance and operational needs of our existing national parks while investing in the routine maintenance that is necessary to prevent projects from becoming deferred in the first place.

Decades of neglect and misplaced priorities have contributed to a $11.6 billion backlog of deferred maintenance in national parks.

The National Park Service recently celebrated its 100-year anniversary in 2016. But as the agency embarks on its second century, decades of neglect and misplaced priorities have left a glaring blemish on a National Park System known for its crown jewels such as Yellowstone and Yosemite. Today, the Park Service faces an $11.6 billion backlog in deferred maintenance projects, an amount five times higher than the agency’s latest budget from Congress.[2]

The deferred maintenance backlog refers to the total cost of all maintenance projects that were not completed on schedule and therefore have been put off or delayed. The effects of the backlog show up throughout the National Park System in the form of dilapidated visitor centers, deteriorating wastewater systems, and crumbling roads, bridges, and trails. Two-fifths of all paved roads in national parks are rated in “fair” or “poor condition.” Dozens of bridges are considered “structurally deficient” and in need of rehabilitation or reconstruction.[3] And thousands of miles of trails are in “poor” or “seriously deficient” condition.[4] More than half of the backlog is transportation-related assets.

In some cases, the deferred maintenance backlog threatens the very resources the National Park Service was created to protect. According to the agency’s recent budget justifications, a leaky wastewater system in Yosemite National Park has caused raw sewage to spill into the park’s streams. In Grand Canyon National Park, an 85-year-old water distribution system frequently breaks, leading to water shortages and facility closures. And campgrounds and lodges at Everglades National Park have been left in disrepair for more than a decade after being destroyed at by a hurricane. From the Great Smoky Mountains to Glacier National Park, roads and culverts, historic buildings, and visitor facilities are in need of rehabilitation or replacement.[5]

Various sources of funding are used to address deferred maintenance projects in national parks. The majority comes from discretionary congressional appropriations. Other sources include Highway Trust Fund allocations, park entrance and recreation fees, concessions fees, and donations.[6]

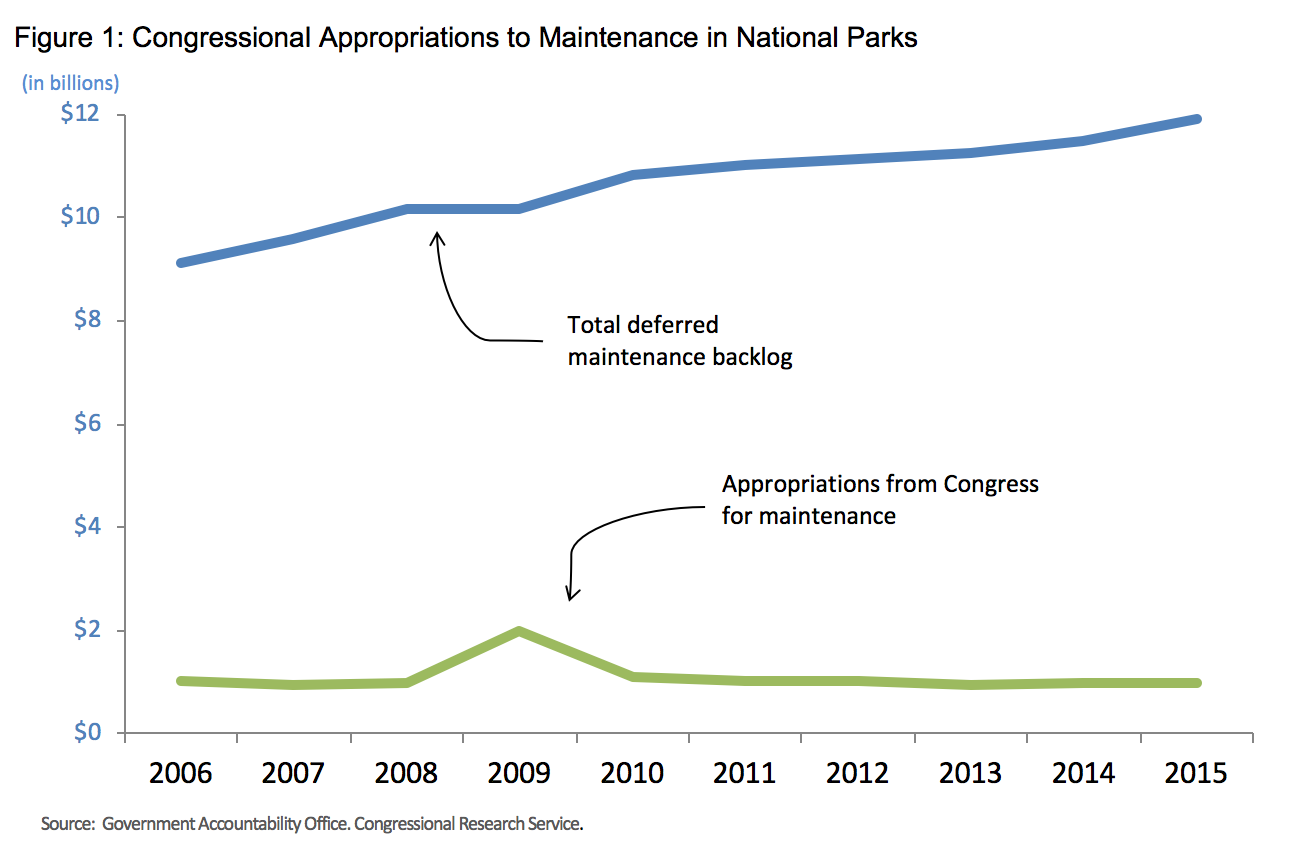

Although congressional appropriations make up the vast majority of deferred maintenance funding, Congress is unlikely to solve the problem through budgetary appropriations alone. Funding for the deferred maintenance backlog makes up only a small fraction of the National Park Service’s annual appropriations from Congress. A recent report by PERC found that from 2004 to 2014, Congress appropriated an average of $521 million each year to projects related to deferred maintenance, or approximately 4 percent of the agency’s total backlog (see Figure 1).[7] The agency has estimated that it would have to spend $700 million per year on deferred maintenance just to keep the backlog from growing.[8]

Instead of maintaining existing parks, Congress has continually expanded the National Park System without corresponding increases in funding.

Park units established more than 40 years ago account for the vast majority of deferred maintenance, yet Congress continues to create new parks rather than allocate funds for existing needs.[9] While recently added parks may not immediately add to the deferred maintenance backlog, the focus on new acquisitions comes at the expense of existing assets. Moreover, today’s new facilities eventually become tomorrow’s deferred maintenance, especially when routine maintenance is neglected.[10]

The basic problem is one of incentives. The National Park Service relies on appropriations from Congress for the vast majority of its funding.[11] But despite providing some annual funding for maintenance, Congress continues to create new parks or acquire more land, further exacerbating routine and backlogged maintenance issues. As former congressman Ralph S. Regula put it, “It’s not very sexy to fix a sewer system or maintain a trail. You don’t get headlines for that.”[12] Since 2000, 35 new park units have been added to the National Park System, yet discretionary appropriations from Congress have remained relatively flat.

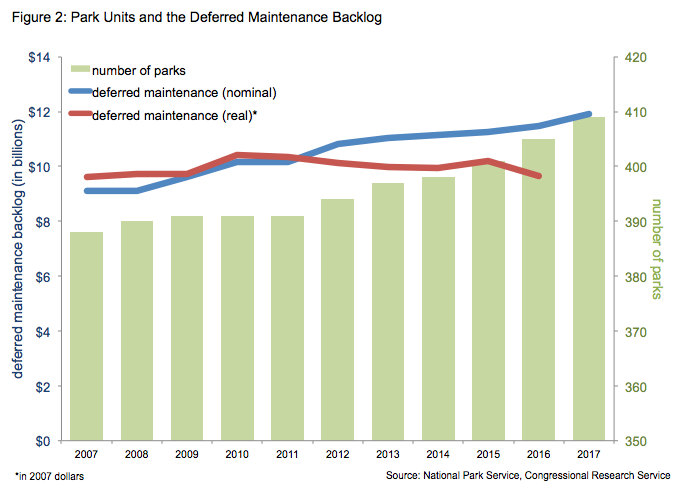

Simply put, relying on congressional appropriations alone is not a practical solution to fix the parks’ backlog problem. In fact, an over-reliance on Congress is likely to make the problem worse because it has been difficult for Congress to secure adequate funding for maintenance needs in national parks, regardless of the political party in power. As a result, the deferred maintenance backlog has remained high for the past decade, with no sign of decreasing. With more parks but little or no additional funding, the National Park System is stretched thin. Unless drastic changes are made, the National Park Service estimates the backlog will continue to increase as new parks are created and existing facilities continue to deteriorate (see Figure 2).[13]

In recent years, several attempts have been made to increase appropriations to deferred maintenance. The National Park Service has repeatedly requested additional funding for deferred maintenance projects, but the amounts appropriated by Congress have been small relative to the size of the backlog. A special Centennial Challenge fund, established by Congress in 2008 to support park improvements, has received approximately $75 million in appropriations to date. These discretionary funds are used to match non-federal donations for “signature” park projects. In 2016, the National Park Service Centennial Act directed senior-pass revenues in excess of $10 million into the fund as well, with deferred maintenance projects a priority.[14] These funding increases, while important, have been insufficient to reverse the deferred maintenance problem.

Local managers know best how to address their maintenance and operational challenges, but they are often restricted in their ability to do so.

No one understands the maintenance challenges in national parks better than park managers themselves. Since the mid-1990s, Congress has granted park officials the authority to address critical maintenance and operational needs without having to rely entirely on annual congressional appropriations. This is done by allowing parks to charge recreation fees and retain the revenues onsite to reinvest in park infrastructure and enhance recreation services that benefit visitors.

National parks have charged recreation fees, such as entrance fees, since before the creation of the National Park Service in 1916. At the start, under the National Park Service’s first director, Stephen Mather, those fees were kept in a special account by the Park Service for road maintenance, park development, and administration. But that soon changed. For much of the agency’s first century, the majority of fees collected at parks were deposited into the U.S. Treasury. Each year, parks relied on Congress to appropriate funds back to the agency. These appropriations were often spent on politically determined projects rather than on the repairs and renovations necessary to adequately maintain parks.

In 1996, Congress passed legislation enabling the National Park Service to keep a portion of the fees collected in parks. Today, the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA) authorizes the agency to retain all park fees within the National Park Service.[15] Under FLREA, at least 80 percent of the fees remain in the individual parks where they were collected, while the remaining amount is used agency-wide without additional approval from Congress.

Fees revenues are important because they provide park managers with a significant and reliable source of funding to address critical needs without relying entirely on Congress for appropriations.[16] They also connect park users with these treasured lands and encourage park managers to be responsive and accountable to visitor demands. In 2017, the National Park Service funded 1,918 projects through FLREA, 840 of which addressed deferred maintenance and improved facilities.[17] In total, the agency has collected approximately $3 billion through its recreation fee program. Last week, in another positive step, the Interior Department announced a modest fee increase at 117 park units, effective later this year, that it estimates will generate an additional $60 million each year.[18]

FLREA was intended to allow park managers to decide how fee revenues should be spent to adequately maintain parks. Yet, in practice, local park managers often face restrictions from the National Park Service on the use of fee revenues for certain maintenance and operational purposes. The agency imposes a variety of internal controls and red tape that complicate the use of fee revenue by park superintendents—limitations that are not described in the FLREA statute. These include prohibiting the use of fee revenues to support permanent employees, various costly approval processes for fee revenue expenditures, and requirements that certain amounts be spent on specific purposes determined by agency officials in Washington rather than local managers on the ground.[19] NPS policy also generally prohibits the use of fee revenues on recurring maintenance and operational needs (as opposed to one-off deferred maintenance projects).

Recreation fees alone will not solve the Park Service’s budgetary problems—fee revenue represents about 8 percent of the agency’s total budget in 2017.[20] But if local park officials are able to freely use the funds they generate, user fees can help improve visitor services, maintain and enhance park resources, and reduce project backlogs. Increasing the flexibility and autonomy of the fee program would also align with the Secretary’s efforts to grant more decision-making authority to local managers rather than concentrating power in Washington.

To reduce the deferred maintenance backlog, Congress and the National Park Service must prioritize cyclic maintenance to prevent projects from becoming deferred in the first place.

At $11.6 billion, the National Park Service deferred maintenance backlog has the potential to overwhelm the agency during its second century. When maintenance is not completed on schedule, it accelerates the rates at which facilities deteriorate. This diminishes the value of park assets and increases repair costs, often as much as three to five times more than if the resources were maintained properly.[21]

Ultimately, to reduce the deferred maintenance backlog, Congress and the National Park Service must prioritize the cyclical maintenance that is necessary to prevent projects from becoming deferred maintenance in the first place.[22] For instance, replacing a roof or upgrading an electrical system at its scheduled time can prevent the assets from falling into disrepair, and therefore prevent them from being added to the deferred maintenance backlog. If prioritized, this cyclic maintenance can be addressed in a far more cost-effective way than if assets are neglected to the point that they become deferred maintenance.

While fee authority can be used to address “one-off” deferred maintenance projects, it does little to address the root of the backlog problem: the continued neglect of routine, cyclic maintenance projects that eventually become deferred maintenance. NPS policy generally prohibits fee revenues from being spent on recurring operational or maintenance needs, instead requiring that the revenues be spent on non-recurring projects (including deferred maintenance). This means that fee revenues generally cannot be used for purposes such as performing regular maintenance of visitor facilities, ditching roads to prevent long-term infrastructure damage, or supporting permanent employees to conduct and oversee routine maintenance. Such restrictions can have the overall effect of exacerbating the deferred maintenance backlog by leaving routine maintenance and operational needs unaddressed.

By restricting the use of fee revenue for non-recurring, non-cyclic projects, the National Park Service is undermining the effectiveness of its fee authority granted by Congress. Park managers can generally only spend their base appropriated funds on routine maintenance and cannot tap their fee revenues until maintenance projects become deferred. As a result, park officials are not making adequate use of fee revenues for everyday operational tasks such as plowing roads, maintaining roads for safe visitor access, and other recurring operational and maintenance needs.

Conclusion

As the National Park Service embarks on its second century, it is clear that new approaches are needed to reduce the agency’s deferred maintenance backlog. Congress should consider several changes to help address the backlog challenge, including 1) prioritizing the care and maintenance of existing parks over new acquisitions and 2) clarifying the fee authority of local park managers to fund maintenance and operations needs of all types on their own without further approval or red tape from Washington.

Conservation, at its core, is about preserving and maintaining what you already own. Congress should seek ways to enhance the care and maintenance of its existing parks before considering additional expansions of the National Park System. In its latest budget proposals, the administration has emphasized its priority to preserve and maintain existing parks and other public lands over new land acquisitions or expansions. Congress should support these efforts to ensure that our nation’s crown jewels are adequately protected before taking on additional maintenance and operational costs through new acquisitions.

In addition, Congress and the National Park Service should clarify that local park managers have the authority to spend fee revenues in a manner similar to how those local officials manage their other appropriated accounts—namely, by leaving it up to the discretion of the park managers on the ground. Local park managers, not Congress or agency officials in Washington, know best how to spend those revenues to adequately maintain and operate parks to enhance the visitor experience. In particular, they should have the flexibility to use fee revenues for cyclic maintenance and other operations that could prevent future increases in the deferred maintenance backlog.

Reducing the deferred maintenance backlog should be a top priority for the National Park Service and for Congress, but the more fundamental challenge is to address the routine or cyclic maintenance that is necessary to prevent park maintenance projects from becoming deferred in the first place.

Thank you again for the opportunity to appear before you today to present my views on this important topic. I hope my perspective has been helpful, and I am happy to answer any questions you might have.

Video of Shawn Regan’s testimony is available here.

Notes

[1] PERC—the Property and Environment Research Center—is a nonprofit research institute located in Bozeman, Montana, dedicated to improving environmental quality through markets and property rights. PERC’s staff and associated scholars conduct original research that applies market principles to resolving environmental problems.

[2] National Park Service, “Planning, Design, and Construction Management,” NPS Deferred Maintenance Report for FY2017. Available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm.

[3] Federal Highway Administration, “2015 Status of the Nation’s Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Conditions & Performance,” Transportation Serving Federal and Tribal Lands. Available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/2015cpr/es.cfm#12.

[4] National Park Service, “Restoring National Park Trails,” Trail Conditions. Available at https://www.nps.gov/transportation/activities_trails.html.

[5] Department of the Interior, Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs, “DOI Maintenance Backlog: Exploring Innovative Solutions to Reduce the Department of the Interior’s Maintenance Backlog,” (March 26, 2018). Available at https://www.doi.gov/ocl/doi-maintenance-backlog.

[6] Laura B. Comay, “The National Park Service’s Maintenance Backlog: Frequently Asked Questions,” Congressional Research Service Report R44924, (August 23, 2017). p. 9. Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44924.pdf.

[7] See Property and Environment Research Center, “Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem,” PERC Public Lands Report, (February 2016). Determining the exact amount of funding allocated to deferred maintenance each year is difficult because funding comes from a variety of budget sources, each of which are also used to fund other activities as well. Moreover, the NPS does not report the total funding allocated to deferred maintenance each year. Figure 1 reports GAO data on the annual amounts allocated for all NPS maintenance, including deferred, cyclic, and other day-to-day maintenance, which averaged $1.2 billion per year between 2006 and 2015. See GAO, “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts,” GAO-17-136, (December 13, 2016). Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136.

[8] “Statement of Jonathan B. Jarvis, Director, National Park Service, Before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, for an Oversight Hearing to Consider Supplemental Funding Options to Support the National Park Service’s Efforts to Address Deferred Maintenance and Operational Needs,” (Testimony of Jonathan B. Jarvis). (July 25, 2013). Available at https://www.energy.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/files/serve?File_id=6D4ED073-B1F5-42CF-A61A-122BE71E67B9.

[9] GAO, “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts,” GAO-17-136, (December 13, 2016). Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136.

[10] “The National Park Service’s Maintenance Backlog: Frequently Asked Questions,” p. 5. Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44924.pdf.

[11] Appropriations from Congress comprised 88 percent of total funding on average for the National Park Service between FY2005 and FY2014. See GAO, “National Park Service: Revenues from Fees and Donations Increased, but Some Enhancements Are Needed to Continue This Trend,” GAO-16-166, (December 15, 2015). Available at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-166.

[12]Michael Janofsky, “National Parks, Strained by Record Crowds, Face a Crisis,” The New York Times, (July 25, 1999).

[13] National Park Service, “Deferred Maintenance Backlog,” Park Facility Management Division, (September 24, 2014). Available at http://www.nps.gov/transportation/pdfs/DeferredMaintenancePaper.pdf.

[14] Laura B. Comay, “National Park Service: FY2017 Appropriations and Ten-Year Trends,” Congressional Research Service Report R42757, (March 14, 2017). p. 3. Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42757.pdf; National Park Service, “Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2019,” p. Overview-3. Available at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY2019-NPS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

[15] 16 U.S.C. §§ 6801-6814. For more information, see Carol Hardy Vincent, “Federal Lands Recreation Act: Overview and Issues,” Congressional Research Service In Focus IF10151, (March 17, 2015).

[16] The NPS estimates entrance and recreation fee collections of $260 million for FY2018. See National Park Service, “Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2018,” p. Rec Fee-1. Available at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY-2018-NPS-Greenbook.pdf.

[17] National Park Service, “Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2019,” p. Rec Fee-2. Available at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY2019-NPS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

[18] National Park Service, “National Park Service Announces Plan to Address Infrastructure Needs & Improve Visitor Experience,” (April 12, 2018). Available at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/04-12-2018-entrance-fees.htm.

[19] For example, the National Park Service recently imposed a internal requirement that at least 55 percent of the fee revenues collected in a park must be spent on deferred maintenance projects. While such a requirement is intended to prioritize deferred maintenance, in practice it limits the authority of local managers to decide how to best spend fee revenues—whether on cyclic or deferred maintenance projects—and could have the perverse effect of creating more deferred maintenance by leaving important routine maintenance projects unfunded.

[20] See National Park Service, “Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2019.” Available at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY2019-NPS-Budget-Justification.pdf.

[21] National Park Service, “Deferred Maintenance Backlog,” Park Facility Management Division, (September 24, 2014). Available at http://www.nps.gov/transportation/pdfs/DeferredMaintenancePaper.pdf.

[22] GAO defines cyclic maintenance as “significant, regularly occurring maintenance projects designed to prevent assets from degrading to the point that they need to be repaired.” GAO, “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve

Efforts,” GAO-17-136, (December 13, 2016). p. 11. Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136.