The Department of the Interior is by far the nation’s largest landowner. Altogether the department manages 500 million surface acres of land, or more than one-fifth of all U.S. land, and oversees the development of oil, gas, and other subsurface mineral resources on more than 700 million onshore acres and more than 1.7 billion offshore acres. In addition, the department’s Fish and Wildlife Service exerts authority over millions of acres of endangered species habitat on private land, and its Bureau of Indian Affairs is responsible for overseeing and managing Native American lands.

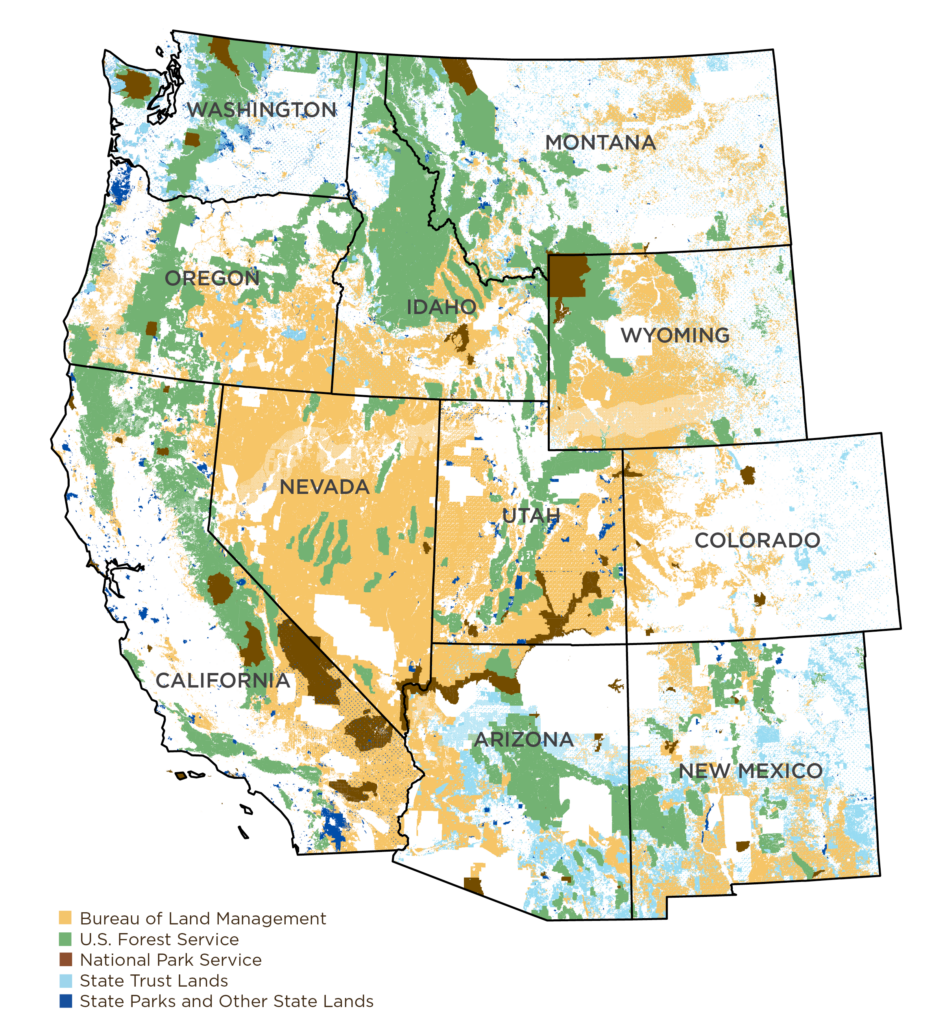

These efforts are overwhelmingly focused on the American West, prompting some to refer to the Interior Department as the “Department of the West.” Indeed, the vast majority of the department’s landholdings are located in western states. In the 11 westernmost states in the Lower 48, for example, the Interior Department’s three main land management agencies—the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service—control 201 million acres, or 27 percent of the total land area. Due to the large extent of these landholdings, many western land issues—from livestock grazing and energy development to timber harvesting and recreation—are matters of federal policy rather than merely of state or local concern, yet they occur thousands of miles from the Interior Department’s headquarters in Washington D.C.

This centralization is largely a result of the Progressive Movement of the early 20th century. During that time, the nation’s natural resources were believed to be best managed not by locals but by experts, primarily located in Washington. This view, however, has since been widely rejected. Nonetheless, our federal land institutions—many of which were created during that earlier time—still largely reflect the Progressive-Era belief in centralized control, as seen in department’s many federal bureaus devoted to efficient management of the nation’s natural resources in the public’s interest through comprehensive scientific planning.

Decisions are often made in Washington D.C., or in the courts rather than by local managers or resolved cooperatively between competing user groups—and that is a recipe for conflict.

Yet this centralized structure of the Interior Department is outdated and impractical today. As economist Robert Nelson has observed, today the Interior Department in effect serves as “a planning and zoning board” for large areas of the rural West, a function that is typically reserved for local and state governments. Across vast swaths of western states, the Interior Department is responsible for seemingly local issues as determining the appropriate number of livestock that should be grazed, which roads and trails should allow for which uses, and where resource development or conservation is most appropriate. Yet in such a diverse and pluralistic society as we live in today, with its various conflicting demands on natural resources—both for traditional “Old West” resource uses as well as for “New West” environmental values—it is increasingly difficult and impractical for a centralized department such as Interior to resolve competing and ever-changing demands in an effective manner.

Because of these challenges, as well as other common problems associated with large-scale bureaucracies such as the Interior Department, our federal land management system today is costly and inefficient. The federal government generally loses money managing valuable natural resources on federal lands, while state agencies that manage similar resources consistently generate net revenues. This is in large part because federal land agencies are burdened by what some land managers have referred to as “analysis paralysis” brought about by a “Gordian knot” of bureaucratic red tape, which increases management costs and hinders agencies’ abilities to respond to changes or resolve competing demands.

Moreover, the Interior Department’s various (and often conflicting) mandates, as well as its ever-expanding missions, creates a lack of clear direction for many of its agencies. This lack of direction contributes to the immense conflict, litigation, and political controversy that surrounds so many public land issues. Today, federal land management is more likely to provoke acrimony and lawsuits than to encourage cooperation among competing users or a sensible balance of multiple land uses. Decisions are often made in Washington D.C., or in the courts rather than by local managers or resolved cooperatively between competing user groups, and that is a recipe for conflict.

The Interior Department has a dramatic effect on the lives of millions of Americans in western states. Congress is right to look for ways to restructure or reform the department to ensure that it is better connected to the people and communities most affected by public land policies and to make it more effective at carrying out its core missions. The ideas discussed below would help accomplish those goals while also improving the overall management and stewardship of federal lands and natural resources.

Greater Flexibility for Local Managers

Federal land management has become an increasingly controversial topic in recent years, even including calls to transfer large amounts of federal land to state ownership. But while a large-scale land transfer is unlikely, there are ways that the Interior Department could adopt new land management approaches that allow for more local management of public lands while retaining federal ownership. In particular, the department could grant local land managers with greater flexibility to develop locally responsive management solutions while still remaining accountable to certain federal environmental and economic standards.

There is precedence for this. For instance, the 2014 Farm Bill provides authority for the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service to enter into “Good Neighbor Authority” agreements with states to cooperatively manage certain areas of federal land. The federal government retains ultimate decision-making authority, and any management actions must comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other federal laws, but the on-the-ground management can be implemented by the states, often much more effectively than the federal government. The state of Idaho, for example, has used this authority to conduct critical forest restoration and thinning projects on federal lands.

As another example, the BLM is currently conducting several pilot projects that will implement a flexible system of “outcome-based” grazing. The core concept is that instead of having the BLM managing every aspect of grazing on a particular federal allotment—such as determining the proper amount of livestock to be grazed and the optimal timing and length of the grazing season—the agency can define certain desired outcomes for an area and then allow local land managers (in this case, the grazing permit holder) to best meet those outcomes however they can.

This innovative approach to land management—defining outcomes and decentralizing control—could be expanded across various agencies in the Interior Department. One similar approach would be to implement a charter land management system, as some have proposed. Charter lands or forests would be owned by a federal land agency but managed under a charter system, similar to the way charter schools function within the larger public education system. The lands would be governed by a board of directors unique to each land unit, such as a grazing district or forest. Boards of directors could be elected or appointed that would be responsible for managing resource and recreation uses within charter area boundaries.

As with charter schools, the core guiding principle for charter lands would be freedom with accountability. Charter lands would be freed from the restrictions of one-size-fits-all regulatory mandates—such as land-use planning requirements and restrictive hiring practices—that produce waste and inefficiency, but they would be held accountable through boards of directors as well as federal oversight combined with stringent standards for charter land performance. Individual land boards would be overseen by a national charter board that would in turn oversee and monitor their performance, ensuring accountability while maintaining management flexibility.

Another strategy is to adopt public-private partnerships that outsource routine management operations of various public lands to the private sector while maintaining public ownership and oversight. Over the past three decades, similar arrangements have proven successful for the U.S. Forest Service, which uses private operators to manage and maintain many of its campgrounds. These partnerships involve performance-based contracts designed so that federal agencies define site rules, parameters for visitor fees, management goals, and maintenance expectations. The contracted lessee collects visitor fees, maintains resources and facilities, and pays a portion of receipts back to the managing agency. Under this approach, private managers have strong incentives to provide good stewardship of the resource and to ensure high-quality visitor experiences since they are dependent upon the revenues they earn to cover costs. Yet they are also held accountable by their contract with the public land agency providing oversight.

A third management innovation is a national park franchising system. If a proposed park warrants national park status, it could be granted the national park title but be owned and operated under private or nonprofit management. Franchised parks would exist under the National Park Service umbrella but would be individually and uniquely designed and managed by nonprofit organizations, businesses, or individuals.

A franchise parks could work as follows: The National Park Service would set franchise requirements, and interested parties would create management plans that align with those requirements. Some franchise parks could also be required to become financially self-sufficient, whether funds were acquired through user fees, partnerships, or donations. A franchise system could give park units the flexibility to manage for local priorities as determined by on-the-ground managers, the protection and status provided by the national parks brand, and the incentives to meet visitors’ desires at low cost.

The Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas is one example of national park unit that is already managed in a similar way. The park unit is managed through a public-private partnership between The Nature Conservancy and the National Park Service. The Nature Conservancy owns the vast majority of the land in the park, but it co-manages the park with the NPS in accordance to its standards.

Grant Park Managers More Authority to Address Local Maintenance and Operational Needs

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has said that the National Park Service’s deferred maintenance backlog is one of his top priorities. Estimated at $11 billion, the maintenance backlog refers to the total cost of all maintenance projects that were not completed on schedule and therefore have been put off or delayed. The backlog is now nearly four times higher than the agency’s latest budget from Congress.

Merely increasing the Park Service’s budget, however, is unlikely to solve the issue. In fact, an overreliance on Congress for funding has likely made the problem worse because Congress would rather create new parks or acquire more land than fund routine maintenance projects. The number of park units managed by the Park Service has grown significantly over the past decade—from 390 in 2006 to 417 today. Meanwhile, the agency’s overall budget, as well as the amount of funding devoted to maintenance projects, has remained relatively constant. With more parks but little or no additional funding, the agency’s resources are stretched thin.

To address the root of this issue, the National Park Service should seek to become less dependent on politically driven appropriations from Congress. Local park managers, not politicians in Congress or bureaucrats in Washington D.C., are in the best position to identify the maintenance projects that are most critical. To do so, the agency should explore ways to rely more on park visitors, instead of Congress, for revenue, as has recently been proposed by the National Park Service. Today, the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA) allows most park user fees to be retained at the park where they are collected, rather than being sent back to the U.S. treasury. That means local park managers can address critical maintenance needs without relying entirely on Congress for appropriations.

More could be done to give park managers the flexibility they need to address critical maintenance issues. FLREA originally expired in 2014 and has since then only been temporarily renewed by Congress on an annual basis. Congress should act to permanently reauthorize FLREA to enable federal land agencies to collect user fees and to expand the discretion of park superintendents to set their own fee schedules without having to obtain additional approvals from Congress or the Secretary.

Make Grazing Permits into Tradable Rights, Even for Conservation Purposes

The Interior Department is responsible for managing a vast system of federal rangelands in the West. The BLM administers nearly 18,000 grazing permits across 155 million acres of public lands. In 2015, these lands provided 8.6 million animal unit months of forage for livestock while also being managed for recreation, conservation, and other multiple-use purposes.

Today’s grazing policies, however, encourage conflict rather than negotiation among competing interest groups. Ranchers have gradually had their grazing permits revoked as public-land policies have shifted toward conservation and recreation and away from grazing, timber harvesting, and other traditional resource uses. Today, the BLM authorizes half the amount of grazing on federal rangelands as it did in the 1950s, and this decline has often pitted ranchers and environmentalists against each other in a zero-sum battle over the western range.

At their core, such conflicts are the result of poorly defined grazing rights and restrictions on trading them. In short, current policies do not recognize grazing permits as a secure property right, nor do they allow grazing permits to be transferred for non-grazing purposes. This means that environmental and other competing interest groups have little or no way to bargain with ranchers to acquire grazing permits, and as a result, disputes must be resolved through litigation or political battles instead of through negotiation or cooperation among local users.

Today’s grazing policies date back to the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. The act requires that grazing permits be attached to specific “base properties”—or private properties that the government deems qualified for grazing privileges. As a result, a grazing permit can have a significant effect on a rancher’s property value. When these properties are bought and sold, the new owner pays for the grazing permit, which is capitalized into the value of the base property.

The law, however, never clarified whether grazing permits are secure property rights. Instead, it refers only to “grazing privileges” while also stating, somewhat vaguely, that those privileges “shall be adequately safeguarded.” The result has been a decades-long fight over the nature and security of grazing rights in the West. Because grazing permits are attached to private properties, and restrictions on those permits can have a direct impact on the value of a ranch, it’s no surprise that ranchers feel threatened by actions that reduce grazing on public lands.

To address these points of contention, grazing policies should be reformed to encourage contractual solutions instead of litigation and conflict. Specifically, Congress should clarify that a grazing permit constitutes a secure property right (or a forage-use right) to a portion of the federal rangeland. In addition, it should make those rights transferable, even for non-grazing purposes such as conservation or recreation.

Congress is right to look for ways to restructure or reform the department to ensure that it is better connected to the people and communities most affected by public land policies and to make it more effective at carrying out its core missions.

Several changes would help make this possible. First, under the current system, ranchers are required to graze livestock on their allotments at their permitted levels or they risk losing their grazing privileges—in other words, it’s “use it or lose it.” If a permittee abandons grazing activities on a significant portion of an allotment, the BLM may be obligated to transfer the permit to another rancher willing to use the allotment for grazing.

Second, the base-property requirement raises the cost of trading grazing permits and restricts who can hold grazing permits. Groups seeking to acquire grazing rights must purchase or already own qualifying base properties to which grazing privileges can be assigned. Removing these requirements would allow permits to more easily be transferable to their highest-value uses, whether that’s grazing, conservation, or recreation.

When property rights are secure, enforced, and transferable, disputes among competing users are more likely to be resolved peacefully, cooperatively, and in a mutually beneficial manner. Clarifying grazing rights and making them transferable for non-grazing purposes would go a long way toward encouraging more cooperation and less conflict over the use of the western range.

Adopt Market-Based Measures to Boost Revenues While Protecting Local Environmental Values

As described above, the Interior Department oversees mineral development on vast amounts of federal subsurface lands. Production of oil and natural gas from these lands generates billions of dollars for national and state treasuries and constitutes 21 percent of U.S. oil production and 16 percent of natural gas production.

The department is charged with responsibly developing energy resources on federal lands to best meet the present and future needs of the public while also ensuring that taxpayers receive a fair return on energy production from federal lands. But uncertainty and delays arising from agency processes, as well as conflicting values with respect to energy extraction and the environment, have contributed to a relative decline in the development of federal oil and gas resources. While oil and gas development on private and state lands has been booming over the last decade, oil production on federal lands has increased only slightly, and natural gas production on such lands has declined.

Given that federal lands containing oil and gas sometimes also offer significant cultural, recreational, and other environmental values, a main cause of the relative slowdown in federal development has been conflicts over resource use. Market-based approaches, however, offer potential to reduce such conflicts, bringing local environmental values more directly into the oil and gas leasing process, and promoting cooperation between energy developers and environmental groups.

The most direct market-based approach to resolve such competing demands would be to open oil and gas lease auctions to recreational, environmental, and conservation interests. Lease terms could explicitly allow individuals or groups seeking to withhold resources from development to hold a lease on terms similar to those that apply to energy developers. When development threatens local environmental values, such groups could coordinate to purchase and hold the development rights to a given property.

Current policies discourage this cooperative approach by requiring that leaseholders must intend to develop their energy leases. If a leaseholder does not intend to develop oil and gas, they in essence forfeit their lease rights. This means that under BLM’s current policies, environmental and other non-development-related interests have few options but to seek administrative delays and further promote the politicization of public land management.

Enabling such a market-based approach to protect important local environmental values would reduce conflict and help ensure energy resources are developed only when they are likely to be more valuable to the public than other competing values. Moreover, such an approach has some precedent on federal lands. In 2013, the conservation group Trust for Public Land purchased an energy company’s federal oil and gas lease rights to 58,000 acres in Wyoming for a total of $8.75 million.

This win-win deal was possible thanks to a provision in the Wyoming Range Legacy Act that allows groups to purchase and retire federal oil and gas lease rights if the lease rights were voluntarily acquired from willing sellers. The provision, however, only applies to certain federal lands in Wyoming. Similar authority could be expanded to allow lessees to voluntarily sell their lease rights for conservation purposes, enabling mutually beneficial market exchanges to occur to resolve conflicts over resource use.

Conclusion

There is much that could be done to transform the Department of the Interior to better address the challenges it faces in the 21st century. Some of the changes discussed here could be implemented by the Interior Department itself, while others would require action from Congress. But in each case, the proposals would help restructure the department to make it more effective, more responsive to the needs of local communities and local land managers, and help resolve conflicting demands through local cooperation instead of political conflict and litigation.

This article is an excerpt of testimony on December 7, 2017, before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Natural Resources of the U.S. House of Representatives.

[donate title=”Support PERC today”]