Here’s a question with a seemingly simple answer: Shouldn’t Native Americans have the same rights to develop their land, if they choose to do so, as other Americans?

That question was the topic of a field hearing held by the U.S. House Natural Resource Committee last week in Santa Fe. The hearing examined how federal control of Indian lands often prevents tribes from capitalizing on their natural resources – a policy based on an outdated notion that tribes are incapable of managing their lands themselves.

Although the government pays lip service to tribal sovereignty and self-determination, Native Americans still lack the same freedoms as other Americans. It’s time for that to change.

For instance, tribes and individual Indians generally cannot own their land. Reservations are managed in trust by the federal government in a manner that Chief Justice John Marshall famously described in 1831 as resembling “that of a ward to his guardian.” As a result, nearly every aspect of Indian land use is controlled by federal agencies.

Even the most basic land-use decisions in Indian Country still require the review and approval of Washington bureaucrats.

But by all accounts, the feds have been lousy managers of Native American assets. A 2015 report by the Government Accountability Office found that poor management and bureaucratic delays by the Bureau of Indian Affairs hinders energy development on tribal lands, resulting in “missed development opportunities, lost revenue, and jeopardized viability of projects.”

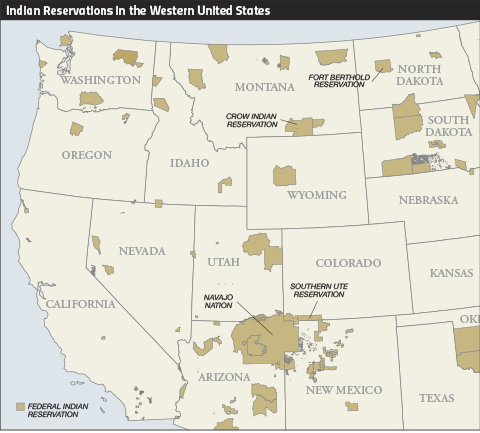

The consequence is that the majority of tribal energy resources remain undeveloped, even when tribes want to develop them for the benefit of themselves and their communities. In one case, it took eight years for the BIA to review energy proposals from the Southern Ute tribe, costing the tribe $95 million in lost revenues. In another, it took 18 months for the government to review a single proposal to develop wind energy on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, causing the deal with the developer and the local utility to fall through.

Regulatory obstacles are often so large that potential non-tribal development partners simply look elsewhere. On Indian lands, companies must go through 49 steps and at least four federal agencies just to acquire a permit for energy development, compared to as few as four steps for projects not on reservations.

Tasks that should be simple, like completing title search requests, result in delays from the BIA. Indians have waited six years to receive title search reports that other Americans can get in a few days.

Not surprisingly, these regulatory barriers raise the cost of doing business with tribes or individual Indians.

For instance, even though the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota are located at the center of the shale oil and gas boom, most tribal members have missed out on the economic growth experienced beyond its borders. Companies would rather drill on nearby private lands than try to cut through all of the red tape on Indian Country.

“Willing and able tribes should have greater authority over energy development on tribal lands,” said Mike Olguin of the Southern Ute at the hearing in Santa Fe. “In some instances, the best way for the United States to uphold its trust responsibility would be to step aside.”

Tribes have demonstrated time and again that they can succeed when the federal government gets out of the way. Consider what happens when tribes have gained control over forestry management on their land. A 2009 study by PERC found that the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana managed their timber far better than the neighboring national forest, both for economic and environmental purposes.

Much more should be done to give tribes the same rights and freedoms that other Americans have. The Native American Energy Act, passed by the House last year, would grant tribes more authority over energy development decisions in Indian Country. Unfortunately, the Obama administration opposes the bill, claiming that it undermines federal oversight of Indian lands, and the president has threatened to veto it if it passes.

Tribes should not develop their natural resources if they don’t want to. But if they do, the federal government should get out of their way. It’s time to stop paying lip service to tribal sovereignty and start giving tribes the same freedom and dignity as other Americans.

Originally published in the Albuquerque Journal (October 10, 2016).