Originally appeared in the Summer 2015 issue of Game Trails, the official magazine of the Dallas Safari Club. This featured column is the second in a series called “For Your Consideration” by Terry Anderson.

Anti-hunters and even non-hunters have difficulty understanding how hunting could possibly contribute to wildlife conservation. They see the animal dead from the hunter’s bullet and conclude that one less animal means the demise of the rest. To the anti- and non-hunter, the hunter’s trophy room with its “stuffed animals” is nothing more than “a victor’s hall of imperial conquest, plunder and braggadocio,” as columnist Lydia Millet described Tucson’s International Wildlife Museum recently in the New York Times.

If they knew their history, of course, the anti- and non-hunters would discover that it was the rise of middle-class sport hunting in the late 19th century which stopped the plunder of wildlife for commercial purposes. From Teddy Roosevelt to the father and daughter going into the field with their trusted bird dog, hunters helped hammer out what has become known as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (NAMWC) and saved America’s wildlife from the “tragedy of the commons” (see box) as seen with the near extermination of the buffalo. Like a pasture open to grazing by anyone with a cow or a pond open to fishing by anyone with a net or rod, open access to wildlife encouraged the race to shoot before someone else did. Understanding the potential for this tragedy, hunters led the charge to close the commons through the NAMWC. Seasons and bag limits set by professional managers and backed by hunters themselves became the tools of conservation.

|

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS The idea that people might overuse resources they don’t own was explained by economist William Foster Lloyd in 1833 and made popular by ecologist Garret Hardin in 1968. Lloyd was concerned about English villages where all local shepherds could graze their sheep. He noted that each additional sheep grazed would benefit the sheep’s owner, but the grazing of each additional sheep would come at a cost of overgrazing for all grazers. Hardin expanded the concept as a metaphor for the global population commons, arguing that each newborn consumes resources at a cost to all others on Earth. What Hardin failed to emphasize and what increasing productivity has demonstrated is that human ingenuity can overcome the tragedy of the commons. This applies especially to populations of fish and wildlife. As long as they are subject to taking by anyone, overharvesting will occur. Overfishing of ocean fisheries is a quintessential example. As with any commons, the key to preventing the tragedy of overharvesting is closing access whether through regulations as with the NAMWC or with private ownership as with fenced wildlife in South Africa. Put simply, the tragedy of the commons and the importance of private ownership can be understood by the phrase, “no one washes a rental car except Hertz.” |

As hunters, we must continue to hammer home the point that we are the conservationists who closed the wildlife commons and helped build the NAMWC. No one can question the efficacy of this model. Elk numbers are at an all-time high in most western states, white-tailed deer in many places are a nuisance, wild turkeys have been reintroduced where they had once been and fish populations generally thrive.

The NAMWC was created from a grassroots movement based on the longstanding tradition in the United States that wildlife belongs to the people − not the king, as it did in England − held in trust by the state. This is in contrast to many European democracies where landowners have retained ownership of wildlife, but the state is still engaged in management. It is even more in contrast with South Africa where the owners of game-fenced properties have full ownership including management authority and where this model is responsible for saving many species from extinction, not the least of which is the rhino.

As a result of the NAMWC, the notion of wildlife being a public trust has become ensconced in American wildlife law. The Wildlife Society, one of the most prestigious professional wildlife management organizations, asserts that the public trust doctrine is “the keystone of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.”

Although we hunters should be proud of our conservation accomplishments, we must be careful not to push the public trust doctrine so far as to create enemies where we should be creating allies. It is true, as John Organ and Shane Mahoney state in the Summer 2007 issue of The Wildlife Professional that “For the Public Trust Doctrine to be an effective wildlife conservation tool, the public must understand that wild animals… belong to everyone.” But when the idea that this holds “regardless of whose property they are on” is carried beyond Organ and Mahoney’s intent, the potential for conflict may be possible between hunters and the landowners who provide wildlife habitat.

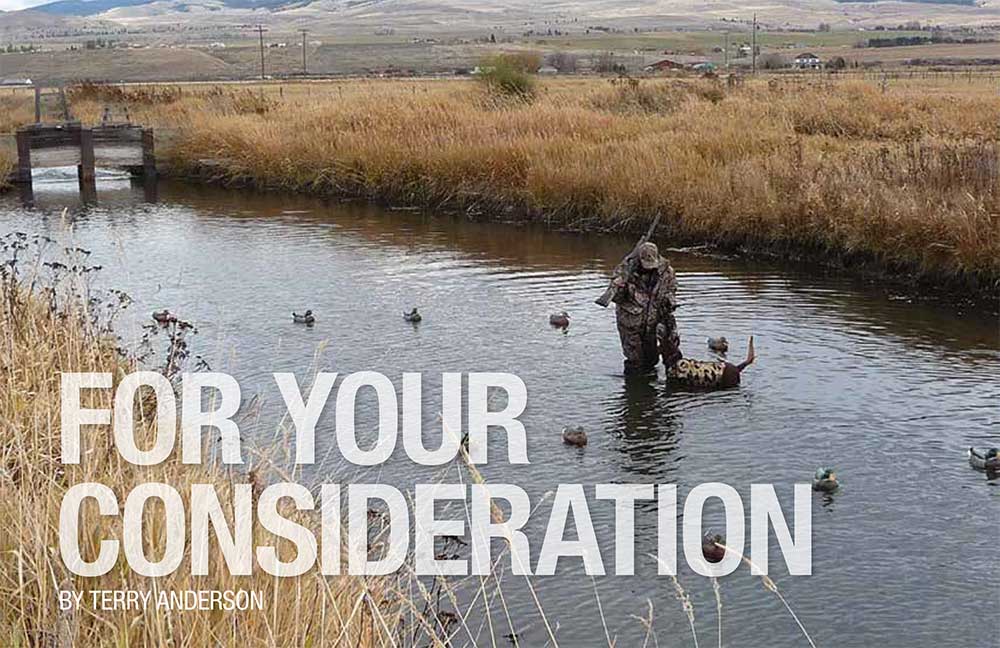

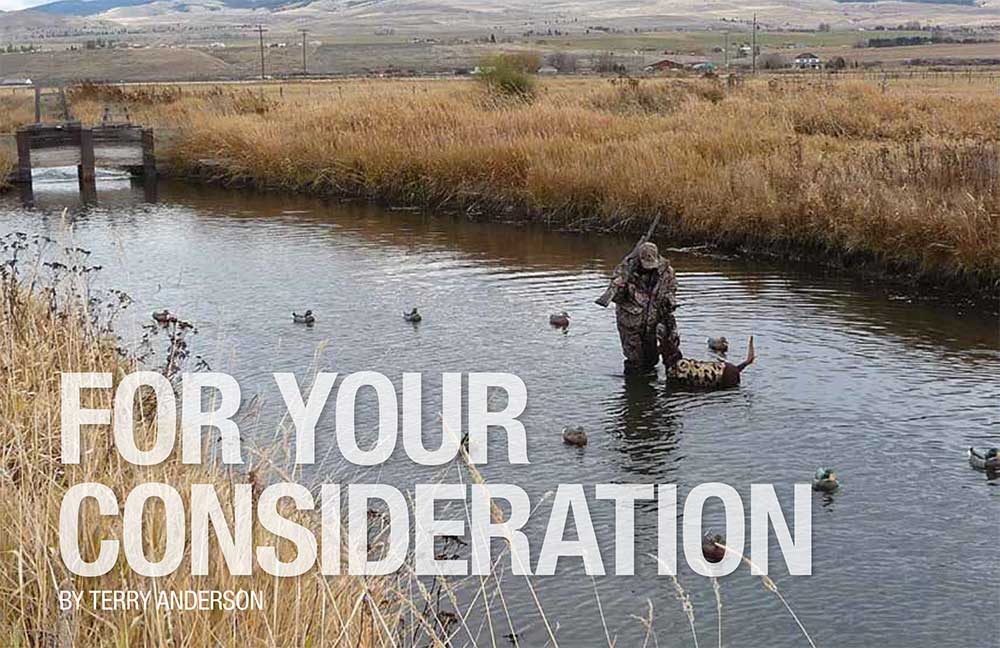

To be clear, Organ and Mahoney were not advocating expansion of the public trust doctrine to include unlimited hunting access to wildlife on private land, but vigilance requires that we consider how such advocacy using the public trust doctrine has been applied to stream access in Montana. Historically, diverting water from rivers and streams for beneficial uses creates a property right in the water. This was the case in the 1860s when farmers and ranchers along the Bitterroot River in western Montana diverted water into their irrigation ditch. Since the late 19th century, the Mitchell Slough − the term used to describe this ditch − has been used continuously for irrigation.

For the rest of the story, see the Summer 2015 issue of Game Trails, the official magazine of the Dallas Safari Club. A PDF is here.