The institute alleged the proposed building site provided habitat for the endangered Indiana bat. After reviewing the evidence, Judge Titus found that Congress, through the Endangered Species Act (ESA), “unequivocally stated that endangered species must be afforded the highest priority” and “that there is a virtual certainty that construction and operation of the Beech Ridge Project will take endangered Indiana bats in violation of Section 9 of the ESA.” Accordingly, the court halted construction of additional wind turbines unless an incidental take permit under the ESA could be obtained. For the portions of the project that were already complete, the court mandated that the existing wind turbines could only operate between November and March, when the bats hibernate.

Although green energy may provide a cleaner alternative than traditional sources of energy, it has its own set of

environmental tradeoffs.

The Beech Ridge case typifies an expanding number of cases where “green energy” generation is curtailed, delayed, or prohibited due to competing environmental goals. There is a growing disconnect between the macro goal of promoting green energy and the micro goal of protecting individual species and specific habitats. Using laws and regulations to pursue environmental ends at the micro scale undermines entrepreneurial incentives to create green innovations within the energy sector.

Green Energy Prospects and Policy

Green technologies such as wind, geothermal, tidal, biofuels, and other renewable sources of energy are touted as endless sources of reliable, clean energy. Concerns about the impacts of air pollution and climate change have created a growing market for green energy. Many utility companies, for example, allow consumers the choice of having a portion of their electricity provided by wind or solar technologies. While some of this utility company activity occurs due to state regulations mandating increased reliance on green energy, there is an underlying market for alternative energy.

Despite this demand, there has not been widespread development of green sources of energy. In part, green energy generation has been stalled by economic realities—green technologies are often more expensive and not as efficient as other sources of energy. Yet, even if the economic factors facing green energy were resolved, recent trends point to a somewhat dismal future for green energy. The reason: The existing legal and regulatory structure does not favor any new energy development.

Environmental Impacts

Although green energy may provide a cleaner alternative than traditional sources of energy, it has its own set of environmental tradeoffs. As noted at the outset, wind energy may impact wildlife. Birds collide with wind turbine blades. Bats generally avoid the blades, but are often killed by the air pressure changes caused by the blades’ rotation. On the ground, wildlife may be frightened by the movement or the noise of spinning turbines, and the footprint of the windmills can disturb critical habitat.

Rather than accept the environmental tradeoffs inherent in green energy production—trading localized costs for regional or even global benefits—some have fought the siting of green energy plants, preferring that such generation facilities move elsewhere. The problem is that the “elsewheres” are limited.

The footprints of solar, geothermal, and tidal facilities may also impact critical habitats. Biofuel, geothermal, and solar energy generation often require large volumes of water. All large-scale land-based green energy generation facilities are land intensive, and large tidal energy facilities require substantial offshore areas, which can impact the aesthetic qualities of undeveloped areas. Biofuel refineries have the additional complication of potentially polluting local air and watersheds. And all sources of green energy face transmission issues. Green energy is often generated in remote areas and must be transmitted from those areas to areas of high demand. Moving electricity often involves building transmission facilities that cross sensitive landscapes.

These facts have created dissonance among environmentalists. Many favor green energy but find its localized impacts repugnant. Rather than accept the environmental tradeoffs inherent in green energy production—trading localized costs for regional or even global benefits—some have fought the siting of green energy plants, preferring that such generation facilities move elsewhere. The problem is that the “elsewheres” are limited.

The Regulatory Setting

Consider the Cape Winds project off the coast of Massachusetts in Nantucket Sound. The Cape Winds project has faced intensive regulatory reviews pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act. The review of this project began in 2001 and did not end until 2009. This process included the preparation of two Environmental Impact Statements by two separate federal agencies. The actual permitting for the project did not occur until the spring of 2010 when 17 federal and state agencies finally signed off on the proposal. Then, the litigation began. Various environmental groups have alleged the project will negatively impact migratory birds and whales, including some endangered species. Local fishermen’s associations have also sued, alleging harm to fish stocks. Now, the project faces a claim by the Wampanoag tribes that the project will take away their cultural and religious heritage by impeding an unobstructed view of the sunrise over Nantucket Sound.

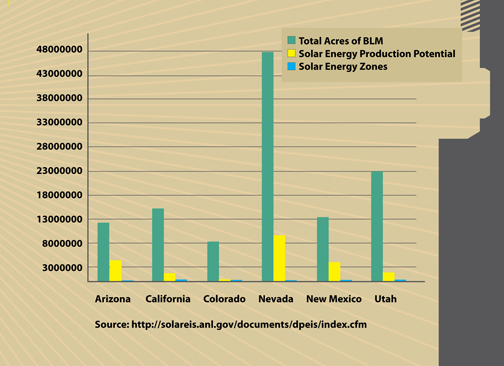

On the other side of the country, the deserts of the southwest provide ideal conditions for large-scale solar generation. Yet groups are already preparing to fight against building such facilities. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) recently prepared a draft Environmental Impact Statement for solar energy sitings on BLM lands in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. The agency first identified areas with physical conditions appropriate for solar energy production that have not already been set aside as Wilderness, Wilderness Study Areas, Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, National Monuments, or parks. Next, the BLM worked with the states to identify lands that could be readily developed without substantial environmental controversy.

This process resulted in the BLM identifying Solar Energy Zones (SEZs), which are a mere sliver—less than .01 percent—of BLM lands in the five states. Even the SEZs, however, have proven to be controversial. A variety of groups presented negative comments during the public comment period on the SEZs. The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, for instance, noted that the Wah Wah Valley— one of three proposed SEZs in Utah—is too close to lands with wilderness characteristics. Other groups complained about insufficient water in the Wah Wah to keep the solar panels clean, which is crucial for efficient production. All told, the amount of non-controversial land available for solar energy production on public lands in the five states presents a dim outlook for widespread solar production in the near future. See figure above

Federal and state regulations reach sufficiently far to impact energy proposals on private lands. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce recently concluded a study examining regulatory roadblocks to energy development and identified more than 300 energy projects currently on hold across the United States. About half of these were green energy projects, the majority of which are on private lands in the eastern United States.

The transition to green energy faces a rocky road ahead. Despite politicians’ willingness to dump large subsidies into green energy generation, there has been less willingness to enact the regulatory reforms necessary to allow large-scale green energy production. Even if and when green energy technologies become economically viable, they will by constrained by regulation. This fact dampens the likelihood that green energy will prosper.