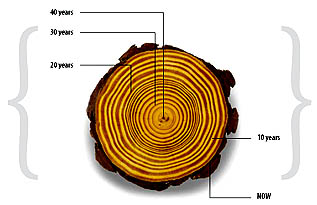

For traditional environmentalists, 2010 is important because the first Earth Day occurred 40 years ago. For free market environmentalists, 2010 is more than an anniversary— it’s cause for celebration. PERC is not only celebrating its 30th birthday, but also the steps taken over the past 30 years that have moved property rights and markets to the forefront of approaches for actually improving environmental quality.

On that first Earth Day, environmentalists didn’t have much to celebrate. In 1970, school children in Los Angeles could not go out for recess due to smog alerts, the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland was known to catch fire, and the bald eagle appeared to be heading for extinction. It was a time for action, so my generation did what they do best—protest.

That first Earth Day not only served as a call to action, it started the new religion of environmentalism. Many environmentalists began to regard human actions toward Mother Nature as an immoral challenge to the natural order, and hence had no qualms to mixing church and state to avoid an end-of-the-world scenario. For the “religious Greens,” federal legislation such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act were the equivalents of the 10 Commandments. These acts command the federal government to put an end to the sins of environmental degradation.

Mainstream economists joined the cause, using their lecterns to preach the parable of the “tragedy of the commons.” They worshiped at the altar of efficiency and followed the teachings of A. C. Pigou, who believed that market failure could be corrected with government regulation, taxation, subsidies, or a combination of all three.

Fast forward to 1980, the birth year of PERC. 30 years ago, a few political economists at Montana State University broke ranks with traditional environmentalists and economists. We were trained in the tradition of the “Chicago school of economics,” which meant we studied markets. As one of our clergyman, Milton Friedman, was fond of saying, we didn’t have faith in markets; we had evidence that they worked.

We were far from the academic ivory towers to the east, yet brazen enough to imagine that we could start a think tank known as PERC in the hinterlands of Montana. Like many other institutes formed about that time, we were part of the “public choice” and “law and economics” revolutions. Our paradigm was built on the shoulders of scholars such as Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ronald Coase, Henry Manne, and James Buchanan.

In those early years, PERC focused more on showing how government failure contributed to environmental problems than on demonstrating how markets might solve them. And there were plenty of examples, from below-cost timber sales to subsidized water projects, which proved government regulation wasn’t always friendly to the environment.

By the final decade of the century, however, we knew we had a better idea. 20 years ago, the small band of “anti-Pigouvians” had become “Coasean rebels,” focused on how property rights could make the environment an asset rather than a liability. In 1991 Don Leal and I published the first edition of Free Market Environmentalism. We highlighted examples of “bureaucracy vs. environment” while building a framework for harnessing markets to improve environmental quality. In essence, we moved from the easy task of documenting government failure to the harder task of illustrating market success. Lacking many concrete case studies, however, we were still writing about hypothetical examples of how free market environmentalism could work.

Partly because there was so much evidence showing that command-and-control environmentalism wasn’t working and partly because PERC’s research was showing that free market environmentalism could work, 10 years ago we launched PERC’s “do tank.” Under the banner of PERC’s Enviropreneur Institute (PEI), originally called the Kinship Conservation Institute, we began to help empower environmental entrepreneurs in the application of property, contracts, and markets to enhance environmental assets. These enviropreneurs have now formed their own 150-member alumni association, which helps guide the curriculum of PEI and maintains a network of practicing free market environmentalists. Each year their stories are showcased in a special issue of PERC Reports.

NOW we are entering the next chapter in PERC’s history. PERC has become a university, in the truest sense of the word, a place where scholars, journalists, policy makers, and environmental practitioners can come together to explore the prospects for and pitfalls of free market environmentalism. It has three departments— research, outreach, and applied programs— each of which offers a variety of ways to “major” in free market environmentalism. Professors, graduates students, and policy analysts spend time as fellows in PERC’s research department, writing articles and books, while maintaining a think tank atmosphere. Journalists and policy makers work in the outreach department bringing life to the projects that illustrate the efficacy of free market environmentalism. And enviropreneurs—real environmentalists and resource managers—come to PERC’s applied programs where they put ideas into action.

Despite huge environmental improvements over the past four decades, environmentalists still can’t get past the gloom and doom of 40 years ago. PERC is taking a different approach by celebrating its 30th birthday knowing it has made a difference. Built on a theoretical foundation laid 20 years ago, PERC started its do tank 10 years ago and now has evolved into PERC University. If you want to be part of this positive environmental force, PERC University is where you ought to be. Enroll today.

In “On Target,” PERC’s executive director Tery L. Anderson confronts issues surrounding free market environmentalism. He can be reached at perc@perc.org.